Let Yourself Be Honey-Tongued

There is poetry in all things if you look for it. Language, and how we speak about a thing, carries incredible power. Language shapes our world view. It shapes our understanding and our relating.

There is poetry in all things if you look for it. Language, and how we speak about a thing, carries incredible power. Language shapes our world view. It shapes our understanding and our relating.

Bees have been beloved to the poets since time immemorial. Sappho, Sylvia Plath, Kahlil Gibran, Pablo Neruda, Emily Dickinson, Maya Angelou, Ralph Waldo Emerson, Mary Oliver, and Antonio Machado to name a few. Indeed to speak well, beautifully, or convincingly is to be “honey-tongued”.

One of the things I hold most dear about the bee shamanism pathway is the craft of poetic speech. Very rarely is anything laid out for you in linear fashion. Every teaching drips in metaphor, poetry, and carefully selected words. Rather than “the infinity symbol”, it is the lemniscate. Rather than “working with energy” we sup of the flower. When we explore language with our honey-seeking tongues, we drape ourselves across the bed of our imagination. Worlds open. New pathways of seeing and understanding occur.

When I say beekeeping, what do you imagine? When I say bee guardian, what do you imagine?

When I say, “a practitioner of bee shamanism can learn to energetically work with their endocrine system”, that’s interesting right? What about when I say, a melissae can become a mistress of her own alchemical garden? Something else happen. I’m roughly talking about the same thing. The first makes a certain kind of sense. You can nod along, say “sure, sure”. The second evokes. It beckons. It hints at much more than energetic work. Something nearly mythic is at play, and you are invited to be part of the myths stalking you. A mythic life doesn’t have any interest in easy explanations.

Bringing the liquid amber of poetry into our language addresses the hole that black and white thinking leaves in us. It is rather anti-establishment. Patriarchy doesn’t love it. Your head of marketing is wringing their hands.

The dominant narrative likes things to be laid out: steps 1,2, and 3. No crooked path through the gloaming. No dalliance in the meadow on your way to market. It’s all “how to’s”, quick fixes, and “7 easy steps to siphon the creative soul right out”.

I’m fairly certain the bees don’t approach life from a users manual. They are infinitely more complex than branded, market-approved language will allow. So are you.

We owe the magnificent creativity of this Earth a little attention to the craft of language. After all, she spins in the black void of the universe, who’s very name hints at the honey-dark stuff that binds it all together: poetry, song, verse.

When I name a course Apis Sophia Exstasis, Entwine, or Betwixt and Between, I’m not trying to be mysterious. I’m calling to the particular poetry of your soul with words from my own. I believe that we are magnetically drawn to that which will call us home to ourselves. Have you ever stopped in a town while traveling just because you liked the name of it? Yeah, that.

Perhaps we could step away from the confines of words that sell, or words that make it obvious, and step into the sensation you feel on your tongue when you speak the name of a beloved softly to the night air.

Maybe then we can start to sniff out the pollen-scented language of the bees.

Food for Bees

Do you feed your bees?

Bees get their nutrients from flowers. Pollen provides protein, fatty acids and minerals, while nectar provides energy through carbohydrates (sugars) and minerals/vitamins.

Do you feed your bees?

Bees get their nutrients from flowers. Pollen provides protein, fatty acids and minerals, while nectar provides energy through carbohydrates (sugars) and minerals/vitamins.

The honey bees’ diet is nuanced and complex, gathered from the diverse floral offering of the bioregion and stored for consumption in the hive.

As bee stewards, we often need to be mindful of nectar sources and potentially feed our bees. Reasons to feed might include: a prolonged drought leading to a nectar dearth, a long winter, a baby colony, and inadequate forage in their habitat.

In conventional beekeeping, another reason to feed you bees is because you took too much of their food and have to feed them so they survive. 🙁

Here’s the catch: in most beekeeping practices people are taught to feed bees sugar. Even if you don’t take too much of their food, you are still expected to feed them sugar syrup for all the above mentioned reasons and also as stimulative feeding. When beekeepers feed bees too early in the spring, it stimulates the colony to start producing more bees. This is because the sugar coming in signals to the queen that there is a nectar flow and she needs to lay eggs for new foragers to be born. Beekeepers do this to get a jump start on spring and build up a bigger workforce toward human aims of production and capital.

The thing is, sugar is not honey. Sugar is not bee food. They can survive of it, but not forever. It’s hollow food. Ultimately, sugar syrup damages their digestion and weakens their immune system. Beekeepers say you can’t feed bees honey because it could contain the spores of a disease called foulbrood. This is true, however, it can be avoided if you know your honey source (talk to the beekeeper your sourcing from) and also know if foulbrood is reported in the area you live in.

If you are going to feed your bees to help keep them alive and support immune health, consider feeding them their own food: honey. If you have to feed them sugar, mix it with some honey or alternate between honey and sugar. Remember, honey is bee food, before it is human food.

You are the Bridge

Where did it begin? This love affair? This obsession? This reverence? Was it in our prehistoric ancestors, with fire in their hands, climbing the highest of heights to gain your nectar? Was it in the way your honey and pollen aided in the development of our ancient brains?

Where did it begin? This love affair? This obsession? This reverence? Was it in our prehistoric ancestors, with fire in their hands, climbing the highest of heights to gain your nectar? Was it in the way your honey and pollen aided in the development of our ancient brains?

Did it begin with those first altars of honey? With those myths of rivers filled with honey wine? With a white she-goat dripping mead? With the tree whose sap means honey and whose promise is life?

There is no tracing the origin of our courtship with the bee. Only honeyroads to follow into and out of antiquity. See the bee nymphs, dusted in pollen, who whispered the art of prophecy to the sun god. See the tears of Ra who fell to the earth and became bees. Christ's tears as well. Hear the hum on the lips of poets. Trace the sisterhood in asterisms. Taste the food of the gods. What about when we wised up? Got rid of all this pagan polytheism? Forgot the Queen of Heaven and chose one god. Did our obsession end? We took Her out of the picture, but did our fascination cease? Ask the priests who brought hives to the new world, because no Catholic mass could be held without holy beeswax candles. Ask the Christian family who brought cake to the bees after Christmas Eve mass. Ask the men of industry and innovation who sought to find a way to better manage this nest of divine beauty. Were they any less mesmerised than Aristotle? Hafiz? King Solomon?

Where has it gone to? This love affair?

Into the many rivers of the inquisitive religion of the modern era: science. That beautiful achievement of the honed intellect. Science, who's “authority has grown so immense over the centuries that it now claims supremacy over all other forms of thought.” (William J. Broad). A gift, this science. And a limitation, if it excludes the old memory of body, poetry, spirit and the ineffable.

What comes next in this love affair? What does the reawakened feminine bringing to the conversation? What happens when we weave centuries of honeyed wisdom with centuries of scientific progress. What else is possible? You are the bridge.

Hymenoptera: veil-winged

Hymenoptera: veil-winged. An order of insects including wasps, sawflies and honey bees, but particularly connected, linguistically, to the goddess culture at its ties to the honey bees. Hymen is derived from Greek and means “membrane” or “veil”. It denotes not only the veil within the virginal maiden, but also the veil draped before in innermost sanctum of the temple of the goddess. It also came to represent the veil between the outer world and the hidden inner world of women’s mysteries, both physically and spiritually.

Hymenoptera: veil-winged. An order of insects including wasps, sawflies and honey bees, but particularly connected, linguistically, to the goddess culture at its ties to the honey bees. Hymen is derived from Greek and means “membrane” or “veil”. It denotes not only the veil within the virginal maiden, but also the veil draped before in innermost sanctum of the temple of the goddess. It also came to represent the veil between the outer world and the hidden inner world of women’s mysteries, both physically and spiritually.

Honey bees are said to arrive with the heliacal rising of the seven sisters, or Pleiades, in the East every spring. Born of the constellation Taurus, the bull, the bees rise in the spring bringing life. The bull is an ancient symbol of the goddess and goddess culture. Through the union of the bees borne of the bull we receive the sustenance of life: milk and honey.

Mirrored in the stars, these seven celestial bees hold the story of the veiled one as well. With the suppression of the goddess culture many myths were rewritten. The seven sisters became seven daughters, one of whom was named Merope or “bee-eater”. She dared to love and wed a mortal and for this she was shamed, turning her face away and dimming her light in the night skies. While every Greek myth has many versions, it’s important to remember they all have threads running back to old memory and old ways that venerate the feminine instead of shame it. In another version these sisters are seven doves, like the doves or priestess that flew out of Africa and founded the three major oracular centers in the Ancient world, including Delphi, where the Delphi Bee gave oracle.

In some myths they were the nymphs of Artemis, who was deeply tied to the bee nymphs (melissae) and the guardian of the wild bees. And in still oldrer, obscure myths the stars were in fact, seven bees: six daughters and their queen, who remains veiled (hidden) in the inner sanctum of the temple of the bee.

Food for thought next time you don your bee veil to go whisper to the bees.

A crown of Ivy

It happens every year. I am on a walk on a warm fall day in November. The kind of day where you start your walk with a hat and a sweater and end your walk in a t-shirt. It’s always the sound that catches my attention. So late in the season, it’s unusual to hear the loud hum of many foraging bees.

Ivy (Hedera Helix)

ifig • efeu • eidheann

Hedera - from Proto-Indo-European meaning “to seize, grasp, take”

Helix - Ancient Greek to “twist, turn”

Main Pollinators: Honey bees, ivy bees, bumble bees, butterflies

Pollen color: Yellow

It happens every year. I am on a walk on a warm fall day in November. The kind of day where you start your walk with a hat and a sweater and end your walk in a t-shirt. It’s always the sound that catches my attention. So late in the season, it’s unusual to hear the loud hum of many foraging bees. Especially when that hum is coming from above you. The bees are foraging on the late winter bloomer: creeping ivy. You know, the kind of ivy that curls up redwood trees or along the brick of old houses? Ivy is found in most of North America, Europe, North Africa and Asia. It spends it’s first 8-10 years focusing on growth, and then turns it’s attention toward flowering.

Ivy Bees in England

I bet you’ve never even noticed the ivy flowers, but the bees sure have. Ivy is a key resource for autumn-foraging bees. While it does provide pollen for many pollinators, honey bees are mainly after the nectar. Ivy honey sets very quickly. Once set, it looks more like crystallized fondant than honey. Bees use this honey as an important food source in the cold winter months. To do so, they have to mix the ivy honey crystals with water to dissolved them enough to be digestible. Humans also harvest and sell ivy honey. To do this they have to slowly warm the honey, being careful not to melt the wax. it’s a tricky process and must be done with utmost care, as to not steal the last of winter stores from the bees.

Ferdinand Leeke

Ivy sometimes gets a bit of a bad wrap. It’s annoying to gardeners and often associated with darkness and “creepy” places such as graveyards. In truth, like other powerfully medicinal plants (seriously, ivy honey is so good for you), ivy has a long history as a plant sacred to the gods. In Celtic lands, Ivy is often associated with the tree alphabet letter “Gort” and carries the serpentine wisdom of transformation within its twisting vines. Throughout Celtic myth and folklore, ivy can be found at the doorway between this world and the fairy kingdom. This is no small thing. The fairy kingdom was more than a place of fancy, it was and is the Celtic Otherworld: a land of mystery, magic and spirit. Ivy marks the doorways where the veil between this world and the world of spirit is thin. They are places to seek wisdom, but also be cautious of, for encounters with spirit can be quite altering.

Ivy is also famously sacred to the god of intoxication, wine and pleasure: Dionysus. Similar to Zeus, who was secreted away and raised on honey by nymphs, the infant Dionysus was hidden from Hera and raised by Nysiades (nymphs) in the ivy-thick woodlands. It is said he was bathed in the spring of Cissusa, meaning “Of the Ivy”, where the waters sparkled like wine and tasted as pleasant. His nymphs and priestesses carried staves entwined with ivy. Dionysus himself wore a crown of ivy, which was meant to protect and guide the experience of intoxication, so that the drinker may only experience the positive benefits of the wine. While Dionysus is commonly associated with drunken revelry, his cult rituals ran much deeper than that. Intoxication does not only come from a heavy night of drinking. One can be intoxicated with spirit and enter a euphoric state. Ivy was not simply a plant of protection, but also a euphoric plant of prophecy. The nymphs/priestesses of Dionysus, known as maenads, were said to be as intoxicated by ivy as they were by wine. It is interesting to note that Ancient Greek brides often carried ivy at their weddings, symbolizing fertility, fidelity and union made in love.

As with most symbols of power, we find a reoccurring theme of polarities. Ivy is associated with death and transformation as well as evergreen life and fertility. It carried both the intoxicant and the sobering effect. It is the twining, serpentine feminine around the sturdy oak and holly king. It guardians the Otherworld and bears it’s nectar to the honey bee, she who fluidly flies between the world of the living and the world of the dead. It brings the transformative powers of deeply altered states and it binds and entwines through the commitment to love.

John Collier - Maenads

Re-piecing A Hive Together

I dreamt last night of a hive torn to pieces. Every bit of comb on the ground was covered in bees. It was the largest hive I’d ever witnessed. Night was approaching and I had to gather all the bees and broken comb. I had to provide them with a new home in a hollow under my bed before it got too cold. Many people around me were oblivious, but some unexpected friends and family came to help. No one had protective clothing. We gently took up each comb with bare hands. Despite the darkness, despite the cold, despite the gravity of destruction, the bees didn’t sting. They understood we were here to help.

I dreamt last night of a hive torn to pieces. Every bit of comb on the ground was covered in bees. It was the largest hive I’d ever witnessed. Night was approaching and I had to gather all the bees and broken comb. I had to provide them with a new home in a hollow under my bed before it got too cold. Many people around me were oblivious, but some unexpected friends and family came to help. No one had protective clothing. We gently took up each comb with bare hands. Despite the darkness, despite the cold, despite the gravity of destruction, the bees didn’t sting. They understood we were here to help.

I was reminded this morning of the delicate balance of relations. A bee, in her nature, stings. It would be unwise to pretend the bee doesn’t sting, the snake doesn’t bite, the lion doesn’t devour. Yet, it would be equally unwise to assume their instinct stops there. All beings also feel. They also have the ability to sense intention. How often have we recounted amazed stories of human interactions with the wild where an animal that should have roared, charged, balked and bit, instead remained still, while the fishing line was removed from her great watery eye, or the steel jaws loosened from the trap?

Our human-centric greed has torn the nest asunder, but it is our very humanness that can defy fear and reach bare handed into the broken system to mend it. You just have to do it. Screw careful planning. Start the garden, risk love, write the book, speak to the trees, march with the youth. The people who join you may not be who you expect. The people who are listening may not have revealed themselves yet. Do it anyway. Mend the nest, mend the weave, mend the rifts despite the odds.

Shamanism Meets Tea Time

I’m about to board another flight to London. I seriously can not wait for scones and tea at No. 9 on the Green in Wimborne. I am visualizing pouring cream into a saucer as I write. Heaven.

I’m about to board another flight to London. I seriously can not wait for scones and tea at No. 9 on the Green in Wimborne. I am visualizing pouring cream into a saucer as I write. Heaven.

I have a suitcase filled with long skirts, a wooden distaff, special rocks, wellies, and an air purifier. Not the most obvious choices for a trip to England. Ok, the wellies get a pass, but they’re so damn heavy and awkward. (Please don’t tell me to wear my weight on the plane. You ever try wearing knee high rubber boots 7 miles over the ocean?) I’m on my way to the Sacred Trust, a school for shamanism, deeply rooted in the Path of Pollen, a European shamanic tradition with the honey bee at its heart. The air purifier is just because I’m allergic to mold. Go figure.

People have started to ask me if I live part time in Europe. I’d LOVE to say Yes, but the answer is, not yet. Since 2010 I have been traveling to the Sacred Trust to study a form of shamanism that survived the Romans, the Dark Ages, and the Inquisition. I equate it to a graduate program. A big investment with my time and money, which is helping improve my mind, body, heart, career and life path. That’s how I justify it to my left brain. My right brain couldn’t give two effs, because this work is 600% soul food.

The school teaches a line of gynocentric, bee-centric shamanism that honors the feminine principal. It is mostly made up of female students, although there are many men starting to take newly offered classes for all genders. It mostly works with bees, but there are serpents, stags and spiders woven in. It is multidimensional and embraces the betwixt and between.

The tradition is a small golden thread. A quiet hum that lasted through the burning of our grandmother’s grandmothers. It’s an answer to my American hunger for spiritual belonging. A hunger that longs for a sense of spiritual roots, but wars with how to be a native Californian without appropriating the spiritual traditions of the Indigenous people of this land. I can not begin to describe the relief I felt when my heart encountered the bee tradition and I cried those soul-aching tears of recognition, knowing that somehow, not all had been lost.

Let’s unpack that for a moment. First and foremost, I need to address privilege. I’m a white, western woman. My ancestors are oppressors and I carry that in my lineage. I refuse to be blind to my own privilege, and as a result of that refusal, I keep discovering ways that I have been. Let me just state that I am learning and I have a long way to go. Also, I fly over an ocean 1-3 times a year in the pursuit of earth-based wisdom connected to the part of my ancestry that was oppressed by Patriarchy and Christianity. So while I resist the dominant social institutions of the former two powerhouses, I am also partaking in the hypocrisy of the entire capitalist, planet-degrading #deathspiral, by using fossil fuels to catapult me in a metal box to a place where I can feel connected to the earth. That’s some real bullshit right there.

Yet, I also subscribe to the idea that there are certain soul places on this earth. Certain spots that speaks to us. Speak through us. Calls us. Awakens us. Claim us. Can a person be OF their native soil and also OF a patch of earth 6,000 miles from where they first touched their feet to the dirt? I most certainly have been claimed by more than one place in my life. Just are sure as I have been claimed by more than one heart. The English countryside is one of those places. And it requires a good set of wellies.

On with further unpacking. When I say I cried because “not all had been lost”, I mean, I am woman and a member of the gender(s) who were and continue to be shamed, maligned, violated and abused for our sex/identity. The wisdom ways of women and the honoring of the feminine in earth-based traditions were nearly snuffed out in Europe’s long history of violence against the life-bearers. Coming to a tradition rooted in my ancestor’s homeland that honors the voice of the womb and the power of the feminine principal is cathartic, to say the least. We ascribe voices to various body parts all the time, but when was the last time you considered the womb to have a voice? Not just the heart, or the head or the phallus, but the womb? Think about it.

Now imagine if you found a place tucked between meadow and forest where you were encouraged speak with that voice. Dance with that voice. See with those eyes. Utter with that yonic intelligence. Imagine relearning your body as though it were flowing with nektars, like a flower. Imagine learning new tongues informed by wind, sea, honey and fire. For those of you who have been wondering why my feed is periodically filled with photos of tea and cobblestones, that is why.

What is The Path of Pollen? I can’t really answer that. It is indefinitely ancient and ever new. It’s part of a very old story. It’s part of writing a new story. Its fingers are made of threads, its head made of stars, its womb made of bees, its longing made of serpents entwined. It is wombic. It is phallic. It is Both And. It is Neither Nor.

I am part of a tradition that stretches its storylines back through the distaff path of ancient Europe. It is a tradition of bee women, known as Melissae, and is very much alive and well in the modern world. The Melissae were the bee priestesses of ancient Greece, most commonly connected to the oracular Temple of Delphi. The Delphic Oracle, also called the Delphic Bee or Pythia (pythoness), was the prophetess for the Earth and of the Earth. It is said the priestesses inhaled the breath of the Dragoness, Python, Gaia’s daughter, and entered a trance, uttering prophecy for all who came to the temple.

I am here to remember how to listen to the voice of the earth, as she arises, a buzz, from within. Ten thousand bees offering nectar on the breath of python. May I be so lucky to glimpse her in the mirror.

And I’m here for tea, scones and whisky, because I’m multidimensional AF.

Dreaming with Nature

The dreams were waking me up at night. Black widows inside my home. Black widows all over the ceiling. Black widows building webs closer and closer to me. No way out. I am not particularly afraid of spiders, although I am cautious of black widows, having grown up in an old 1930s home. I tried to reason out why I was having these nightmares. I read about black widow symbolism. I questioned my relationship to spider, web and venom. For two weeks my nights were filled with the dark ladies. Then, one morning, after other terrifying infestation dream, I opened my eyes and said aloud “It’s my bees. There is a black widow inside my hive.”

The dreams were waking me up at night. Black widows inside my home. Black widows all over the ceiling. Black widows building webs closer and closer to me. No way out. I am not particularly afraid of spiders, although I am cautious of black widows, having grown up in an old 1930s home. I tried to reason out why I was having these nightmares. I read about black widow symbolism. I questioned my relationship to spider, web and venom. For two weeks my nights were filled with the dark ladies. Then, one morning, after other terrifying infestation dream, I opened my eyes and said aloud “It’s my bees. There is a black widow inside my hive.”

It was my first year keeping bees, and at the time I did not know how common it was to find black widows and other eight-legged in or near a hive. It makes sense: honeybees must be a real juicy meal. I told the bees I’m coming, and dawned my gloves and veil. Sure enough, she had taken residence in the back of the hive, fat and deadly. The bees couldn’t expand their nest, and they were living with a predator. The bees had let me know what was going on, and I finally got the message. I was dreaming with bees.

This was my first experience of consciously experiencing communication from the natural world through dreams. In an age where talk therapy is our chief modality for addressing emotional and mental states of unrest, dreams become entirely self-centered. We defer to the modern day agreement, that dreams are our subconscious at best and the detritus of our day at worst. Don’t get me wrong, I love and have benefited from talk therapy and the psychoanalysis of dreams. I think both have a very useful and important place. I would agree that many dreams are the product of our subconscious knocking about. But what if it’s not always our subconscious claiming a seat at the table? What if Fox is knocking at the door with a wink and a swish of his tail? What if Raven is keeping a steady eye on your dreamscape, daring you to ask her a question? What if your ancestors, in their moon-white bones, are clattering around the house rearranging the furniture? To get to the point, what if we are not just dreaming “of”, but dreaming “with”?

I have dreamt with my bees since this first visit. Sometimes they heal me. Sometimes they cover me with honey. Sometimes with sting. Sometimes they share things that are about me, and sometimes they are about the bees. I had a hive visit my dreams and inform me of it’s passing shortly before it died. I had another black widow dream and once again, went looking and found the same. Even disregarding my personal relationship to bees, is it so much to imagine that the wild might be reaching in to touch us? From a shamanic perspective, dreams are a way to work directly with the spirit world. What would the spirit world be without the language of the wild? Nature is our interface with Spirit. It is the color palate and Spirit is the hand the moves the brush.

When we invite the pad-footed spirit of the wild into our dreams we are asking to be worked. As mythologist Martin Shaw says, we are being dreamt. In my Dreaming with Bees course, I make it clear that we are not seeking to dream of bees. I am asking students to invite the bees into their dreams. To dream with the bees. Whether you dream of bees or not is a mute point. It is about the courtship with a nature ally, with a spirit and with a fellow living creature. The living earth is dreaming her way into being, and we are dreaming with her. If only we could break free of the ecological nightmare we’ve created and remember our body is her body.

People ask me all the time, what does dreaming have to do with beekeeping? Why do you teach beekeeping and dreaming classes? The answer is this: whether we know it or not, when we set up a hive in our garden, become a player in it’s story, and share in it’s vital resources, we are seeking kinship. Some conscious or not-so-conscious part of us is reaching out to a species that has been an enigmatic friend to mankind since prehistoric times. A species that has never and will never be fully tamed. A guardian at the gate to the wild. An emissary between the worlds. To know this creature, we have to do everything we can to break away from conventional beekeeping practices and the man-conquers-nature/woman mindset. To do this, we must find the crooked, forgotten paths deep in the woods. The ones that twist out of sight and have no guaranteed destination. These are the paths of our animal memory. Our ancestral memory. Our indigenous selves. The observer. The shaman. The Seer. The Dreamer. The Wise Woman. The other ways of knowing. The ways that speak in pine groves, antlered visitors, ocher and sun on bare skin. We dream with bees, because we are dreaming ourselves back home.

Dreaming with Bees Summer Session Tele-conference course begins Monday August 7, from 5-7pm PST

Stalking the Wild Feminine

It’s going to be hot out there. No-option-but-naked kind of hot. Snake weather.

The bees will be gathering water from the banks of the Eel. The water ouzel will be dancing her grey-winged hop up and down the river. The bears wont come near. There are too many of us.

It’s going to be hot out there. No-option-but-naked kind of hot. Snake weather.

The bees will be gathering water from the banks of the Eel. The water ouzel will be dancing her grey-winged hop up and down the river. The bears wont come near. There are too many of us.

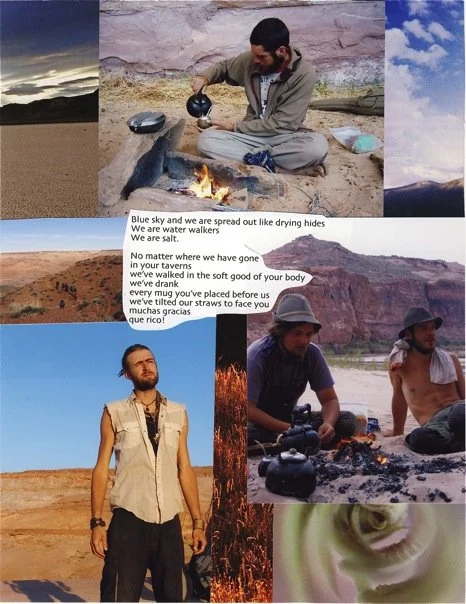

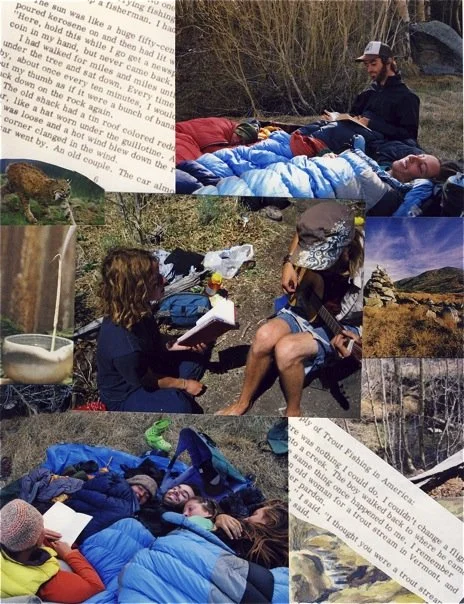

Tomorrow I’m going backpacking with thirteen dear friends. A reunion in the California wilderness. Ten years ago, we piled our bright eyes and burgeoning adulthood into a few likely-to-fail vehicles and set out on a four and a half month journey into the wilderness. I wouldn’t exactly call is a backpacking trip; it was less hike-through and more wilderness emersion. Alumni and friends of the Sierra Institute program, we went to learn about ourselves from the wilds and each other.

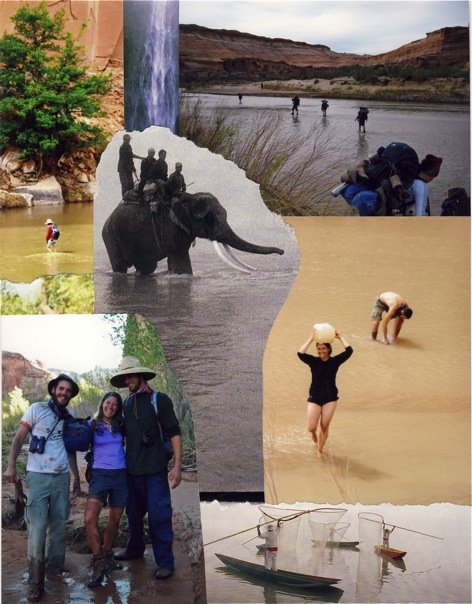

Three weeks fishing in the Marble Mountains, two weeks tucked under dripping canyon alcoves on the Dirty Devil river, three weeks following the creek lines through the frosty Whites, five days with grandmothers and ceremony in the Sonoran desert, twelve days vision fasting on the Kaibab Plateau with the School of Lost Boarders, a week along the sea battered edges of the Sinkyone. We sat in council, we ate wild watercress and wood sorrel, someone got lost for three days, people shared backcountry romance, people got sick, people got fed up and left, we disagreed, we laughed, we read stories aloud, wrote songs, met bears, wiggled into backcountry skin, made amends with our nature-starved souls, and broke ourselves against modern society.

We’re going back now. Thirteen busy adults with busy lives, affording ourselves four days to pay homage to four months of life altering earth-speak. For me this means snakes. Rattlesnakes. I find it a terrible irony that my favorite place in the wilderness is also one of the most snakey out there. To further the cosmic joke, I was born for wild places, yet life offered me a highly traumatic early childhood experience with death and a rattlesnake. Fast forward through twenty years of snake nightmares and debilitating phobia, and you find me dawning a heavy pack, hyperventilating in an Arizona parking lot, and hoofing it into the snake-rich springtime desert. I would not be defeated by phobia. I would stalk the wild feminine and surely and she stalks me.

Now, I am versed in venom. A woman of the bee, stung time and again. Since that journey, when I came face to face with my nightmare pursuer, I have negotiated a new relationship with bite and sting. I am not less afraid, but I less crippled. I am more whole. It has something to do with learning the language of dreams. With learning to read the story differently. Why does the serpent bite me, pursue me, threaten my sleep? Could it be the old magic, the earth magic, seeking a way in?

The Bees became my bridge to the Snake. In their hidden way, they revealed the old stories about the sacred serpent. She who moves through the earth. She who is pure creative power. Pure sexual life force. The embodiment of the divine feminine. In ancient Greece, the Oracle of Delphi, she who famously uttered prophecy, was known by two names: the Delphic Bee and the Pythia. She was a Melissae, a bee priestess, but she was also of the serpent, the earth-dragon. Pythia is a Greek name derived from Pytho, the old name for Delphi and our root for the snake species, Python. Pytho or Delphi was the center of Gaian mother culture; the navel of the world. This center point was represented by a stone, the omphalos, an egg-shaped carving guarded by Python and used in the uttering of prophecy.

John Collier [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

As Patriarchy made it’s way into Greek culture, the Pythoness became a monster. Apollo, the sun god, slew the serpent and Pytho became the Temple of Apollo. The divine feminine force was overthrown, shamed, violated and erased. So, we have another story of how we split ourselves from the natural world. How we took the wholeness of human expression and divided it, driving the stake down through our own sense of who and what we are. Divorcing man from nature. Woman from man. Sexuality from the sacred. The female form, she who knows the language of the serpentine flow, is exiled from the holy. Exiled to the point that today, in American politics around health care, simply being a woman is considered a pre-existing condition.

It is no wonder that I have been stalked through my dreams by the snake. From a shamanic view, to be bit by an animals in dreams, often signifies taking on the animal's specific powers or medicine. It is an invitation, never mind how terrifying. When we dig in to the storied myth-lines of our dreams, when we look at them as more than simply the psychological detritus of our day, we find breadcrumbs towards a fuller expression of self. We find that the antidote is venom, and the poison is our own disconnect between self and nature.

I talk to my bees. I ask them to teach me. I dream with them. I dream of them. They show me through sting, nectar, pollen and hum how to be a more embodied woman. Let's call it earth magic. Tomorrow I will set out on the trail, and have my conversation with the snakes: “You’re beautiful. I love you. I love the way you move. I will not harm you. I am afraid of you. If you choose to show yourself to me, let it be gentle. I love you.” Who knows if it does any good, but it places me firmly in my body, and I begin to weave my way back into Wilderness Self. Perhaps our wild feminine needs to be approached as such, aware of the long exile and the fear that comes from not knowing how to be around a force of nature that is so powerful. Even when that force is expressed through our very form.

You’re beautiful. I love you. I love the way you move. I will not harm you. So mote it be.

Honey Bees as Heart Healers

We women of the bee work in cycles of six. Six-sided, six threads, six sisters, six revolutions. Six years. On this day, six year ago, I found out I was pregnant. It’s a old story really, one that’s been told before, in different words by different women, but it’s also my story with the bees, and therefore, it has a place here. I found out I was pregnant because of a dream. Not my own; that of a friend.

We women of the bee work in cycles of six. Six-sided, six threads, six sisters, six revolutions. Six years. On this day, six year ago, I found out I was pregnant. It’s a old story really, one that’s been told before, in different words by different women, but it’s also my story with the bees, and therefore, it has a place here. I found out I was pregnant because of a dream. Not my own; that of a friend. On this morning, six years ago I woke feeling dizzy and out of sorts. I phoned up a friend, who gently informed me that she had a powerful dream. “There’s nothing wrong with you honey," she said. "You’re pregnant.” The spirit of my daughter had come to her in a dream the previous night asking her to tell me about her and remind me to trust.

In that moment, standing dumbstruck on a busy sidewalk, I felt the most euphoric wash of warmth spread over me, and I understood unconditional love for the first time. I knew she was right. I was pregnant. It was the happiest moment of my life.

Three months later, I lost the baby. She left on a spring day when a late April storm brought fat, lazy snowflakes drifting down on the roses lining the hospital courtyard. I spent two days in that hospital, on the maternity wing, loosing my baby while listening to other babies being born between bouts of sleep and an emergency surgery. I dreamed then, during surgery, of myself giving birth while the spirit of my lost daughter acted as midwife. We were in ancient Greece, surrounded by women and the scent of beeswax and crushed herbs. I was in an order of priestesses that worked with the principals of parthenogenesis. I heard again to trust. It was year later, when I found out these priestesshoods actually existed and that many were associated with the Melissae, or honey bee priestesses.

A recovery bed was prepared for me in the guest room of my parent’s home. A bed which shared a wall with a colony of honey bees. You see, the summer prior, I had gone to The Sacred Trust in England to study with a British shamanic tradition called The Path of Pollen. My introduction to bees was not in fact through beekeeping, but rather through a very old tradition that sees the women of its ways as Melissae, Greek for Honey Bees. While I was in the UK, a wild colony of bees moved into a hole in the exterior wall of my parents home. They built honey comb and raised their young in the space between my recovery bed, and the outside world. The bees kept me company through the darkest hour of my life.

Miscarriage is common. It’s a story that countless women carry in their bodies and memory, but it's not a thing we talk about very often. We are told it’s common, that we’re probably still fertile and to try again. What isn’t included is that for some women, it can include postpartum depression and PTSD, not to mention the unyielding torrent of grief.

I buried what was left of my pregnancy in the garden, beneath an new, empty beehive I built myself. I prayed to the spirit of my baby to bring me bees so that I could be a mother to something. Three days later, I received a call about a swarm. It was my first. The swarm was hanging in the shape of a heart from a blossoming apple tree. Honey bees swarm are an act of reproduction, a great issuing forth of fertile optimism. It happens in the spring, once hives have made it through the long dark winter and new forage abounds. The colony prepares the hive mother (queen bee) for flight and waits for an optimal spring day to rise from the hive is a swirling cloud of wings. A third to half of the hive will leave with the initial spring swarm and fly to a nearby perch, such as a tree, where they will hang in a cluster until a new home is collectively agreed upon. The remaining bees inside the hive will raise a new virgin queen and life will proliferate. It is a truly magical event to witness.

Six years ago I became a beekeeper. A bee mother, in as far as one can mother a highly intelligent super organism that’s been thriving for thousands of years without human intervention. A bee guardian perhaps. Or rather, I fell in love. For me, they became the anchor through which I slogged through PTSD and heartbreak. They kept me tethered to life, when on some level, I just wanted to bleed out. They taught me about the honey and the sting. They were patient with me. They forced me to be present, and sharply brought me back to my body if I drifted. They permeated my dreams. The hummed the song of life, fertility, forgiveness and order. The bees made sure I kept feeling.

The grief story is a human story, and a story we all share. As author and teacher Sobonfu Somé says, “We need to begin to see grief not as foreign entity and not as an alien to be held down or caged up, but as a natural process.” So here I am, still grieving someone I never met. Here I am with tears of the empty womb, for the lost ones, for the motherless ones and the childless ones. Here I am, sitting at the precipice of another swarm season and wondering at the strange synchronicity of life. Wondering about what makes you a mother and when does it count to call yourself one? Is it when your baby is born? Is it when you conceive? Is it when bring a child into your home? Is it when you say yes to raising and caring for another life form?

We bee women work in cycles of six, and today marks six years. Today things are more piercing than usual. Today the memory is close, and the journey of healing is arching out behind me in its multitude of colors. Since that day, when I discovered I held the most precious spirit within my womb, I have started a business dedicated natural beekeeping, initiated dream workshops centred around the honey bee, worked intimately with women and their womb-stories, traveled multiple times back to England to train with The Path of Pollen and found home in a new city. In one week, I will embark on my sixth trip to England to study once more at The Sacred Trust.

Moving into my sixth year as an apiculturist, I am acutely aware of the gift bee-centric beekeeping can be to the beekeeper. Bees can be a bridge between ourselves and the natural world. A way to address the collective grief of nature-deficit disorder by engaging with a species vital to the weave of life on this planet. A way to serve. Beekeeping has been utilised to treat PTSD in veterans and assist in nature-based therapy for inmates in prison. It offers a reason to watch the seasons, to connect to the cycles of life and flowering plants. Without meaning to, we become aware of the fertility of the earth, the places we need to tend and coax into thriving, the places that offer prolific life-sustaining nectar. We hear the hum of a healthy hive, and we are soothed, even if we don’t understand why.

So often, my question is how do we serve the colony? How do we become bee-centric, and not human-centric? How do we see through the lens of the bee. But bee guardianship is a relationship, a two way street, an agreement. Every once in a while, I take a moment to remember the grace of what the honey bee offers us, because, she is after all, central to the fecundity of all life.

My daughter’s hive lived for four years, dying during the summer I moved away. Now, a tree is planted on the site of that old womb/tomb. I became a bee guardian because my womb needed to heal. Because my heart needed to know about the other side of grief. Because even in sorrow, the bees bring me immeasurable peace. Because every day that I grieve my childlessness and dream of a new womb-story, I am also reminded that there is an ineffable joy in the love between a bee and a flower. From that love the earth remains a fertile mother, showering her children in meadows.

The Big Bad Varroa Ally

This morning I sat in a garden teaming with the birds and the bees. Humming birds noisily darted between creeping vines of nasturtiums, red raspberries hung plump and inviting from semi-orderly thickets, honeybees swooned in the fuzzy clumps of borage, and zucchini’s performed their summer competition for Most Alarmingly Large Vegetable.

This morning I sat in a garden teaming with the birds and the bees. Humming birds noisily darted between creeping vines of nasturtiums, red raspberries hung plump and inviting from semi-orderly thickets, honeybees swooned in the fuzzy clumps of borage, and zucchini’s performed their summer competition for Most Alarmingly Large Vegetable. I was at Wildflour Bakery, a jewel of fresh baked bread and Goat Rock Roast Coffee a lazy drive down Bodega Highway. While it does have it’s downside (read: Optionitis for those who dare to choose only one loaf), it’s a not-so-secret favorite secret spot in my new home of Sebastopol, California.

I nestled myself into a garden bench with a Butternut Squash and Gouda scone and proceeded to read a most unpleasant article, but thought provoking article.

The article was titled "The Colony-Killing Mistake Backyard Beekeepers Are Making”. Let’s start there. I steer away from articles that promote fear and shame on the outset. This type of headline is mean to make you worry before you even click on the link. However, a natural beekeeper once told me that she does her damnedest to stay abreast of the conversation. She reads new research, seeks varying opinions and strives to be as educated as possible, so that when she faces a room of conventional beekeepers and states that she doesn’t use treatments and her hives are thriving, she can back the guffaws and protests of the impossible with observation and research-based knowledge.

My morning read didn't have a lot of meaty substance to it, but the thing got me thinking. It was one of the many articles I’ve seen admonishing backyard beekeepers for refusing to treat their hives with chemicals, organic or other. It speaks to the dangers of allowing mite populations to flourish, infecting other colonies for miles around and putting the species at risk. It speak to a desire that every backyard beekeeper at the least, consider chemical treatments. Miticides are, as we know, the tried and true, scientifically studied method for saving the bees.

In a video by the Rucher Ecole, treatment-free beekeeper David Heaf states “putting chemicals in the hive doesn’t just contaminate your hive products. The honeybee is susceptible to some of the miticides....It’s just trade-off against the damage to the bee and the damage to the mite….But worse still, because some of these actors are kinds of antiseptic, they seriously disrupt the microbiological environment in the hive. Bees hugely depend on the other organisms, the microorganisms in the hive, for a healthy ecology of their hive, for the health of their young and the health of themselves."

Despite such encouragement toward treatment-free beekeeping, I used to struggle with what to do. I used to ring my fingers over whether or not I should get on board and just treat my bees. I used to ask myself if not treating my bees was a form of torture. I asked this because a highly regarded local beekeeping authority from my home town of Nevada City, CA told me it WAS a form of torture. He told me the people from Marin and Sonoma who practice Natural Beekeeping were “The Taliban of Beekeepers”. Needless to say, I never went back to another one of his classes.

I began to seek out other kinds of beekeepers. I found people like Corwin Bell, Heidi Herrmann, Gunther Hauk, Michael Thiele and Jacqueline Freeman. I went looking for those “terrorist” beekeepers the man in Nevada City so aggressively disliked. I found places like The Melissa Garden in Healdsberg, CA and The Natural Beekeeping Trust in England. I started to find my kindred spirits of the bee world. Bee Guardians who have raised bees without chemicals or antibiotics. People who had, against all mainstream belief, manage to raise healthy, lasting colonies. Honey bees that even co-exists with varroa.

What are they doing different? Why do their bees thrive, despite the odds? While each natural beekeeper’s practices are different, I began to notice certain commonalities (generalizing here): they allow swarming, breed strong genetics, talk to their hives, adopt alternative hive styles, harvest much less honey (if any), plant for pollinators, rid their gardens (and neighborhoods) of pesticide use, don’t feed bees sugar, and keep their bees in one place. In short, they listen to nature. They listen to the bees.

What I find again and again, is the health of the colony or apiary is directly related to the health of its environment. Humans and bees are not so very different. Our health suffers in emotionally, physically, mentally or spiritually stressful environments. The very foundations of conventional beekeeping practices are part of what is harming our bees. I’m not a scientist, I don’t have proof. I am one of the billions of lifeforms, who’s shared birthright is this planet, who can feel the places we are out of balance and seeks to right that balance by listening to the Earth.

If that’s a little to loose for you, try this: pesticides actually do kill (they are design to) and if you want healthy bees start by eradicating pesticide use from your seeds, your garden, your neighborhood, your country, your planet.

Returning to my morning garden moment, as if on point, in my caffeine-induced, bee-advocate reverie, I heard a British woman exclaim, “There are just so many bees here! I love the bees! Isn’t there a kind of pesticide that’s hurting them?” Without thinking, I shouted through a patch of sunflowers, “Neonics! I mean, yes, there is. Sorry! Didn’t meant to interrupt. I’m a beekeeper. They’re called neonicotinoids.” She looked at me blankly, after which, I thoroughly retreated back into my unassuming bench, and read on.

There was one more particularly crunch paragraph in the article that caught my eye. "Bees face other challenges beyond mites, including poor nutrition, disease and pesticides. Even veteran beekeepers say it takes more effort to keep their bees alive these days.”

I had a little chuckle to myself. Yup, other challenges. It comes back to our very Western way of thinking: treat the symptom not the cause. Varroa is a symptom of a much larger dis-ease in our pollinator communities. What if, instead of looking at Varroa as a monster, we looked to Varroa as an ally? The dark shadow-self that comes forward when we need to look at something we have been unwilling to see? An aspect of the entire ecosystem that has it’s place in the larger story. Some piece of our own wholeness that has gone out of balance and “appears” as a demon (ok ok, a mite), but is really just a way our inherent wisdom is communicating with us. I know I’m making metaphors between the human psyche and beekeeping. Just be cool with it. I’m a beginner. I know a whole lot about bees and will probably never stop being a beginner. This is the way of learning the natural world.

The truth is, when it comes to beekeeping, colonies that come from treated parent colonies are going to have a really hard time making it through without treatments. These are bees that come from packages and nucs sourced from large-scale conventional beekeeping operations after the hives have traveled to the California almond pollination event in early spring. They are often not coming from a healthy environment, have been fed sugar, and are of weaker genetics than naturally raised or feral hives. As a beekeeper helping other backyard beekeepers get started, this question of source is ever-pressing. How do I help bees coming from treated colonies make the transition to treatment-free beekeeping? I wish we could all set up apiaries and naturally breed our own strong colonies, but alas, there are still too few beekeepers trying things the old old old school way. I will keep asking this question, because I believe in backyard beekeeping, and I believe it can do much more good than harm.

In the mean time, grow your gardens without pesticides, plant for pollinators, educated yourself, and sit next to your hive. Grab a cup of tea and sit there a long time. Sit there until the Mad Woman of the House goes quiet inside. Sit there until the life-hum whispers a sweet honeyed language into your heart. Sit there until you are bored. Sit there until you realize, without noticing, a great calm has descended upon you. Sit and talk to your bees, for I promise, with absolutely zero science to back me up, they will most certainly talk to you.

How to Get New Bees

In Northern California there is still snow in the hills and rain on the weather forecast. However, despite the winter chill, it’s time to start thinking about getting bees. Regardless of where you live, late winter is the time most local bee breeders start selling bee packages and nuc. You wont receive your bees until the spring, but if you want to ensure you’re going to get bees this season, it’s best to buy them now.

In Northern California there is still snow in the hills and rain on the weather forecast. However, despite the winter chill, it’s time to start thinking about getting bees. Regardless of where you live, late winter is the time most local bee breeders start selling bee packages and nuc. You wont receive your bees until the spring, but if you want to ensure you’re going to get bees this season, it’s best to buy them now.

This year was a particularly devastating year for colony losses across the board. Both chemically treated and untreated colonies suffered. In California, the severe drought helped to encourage monstrous mite populations. Couple this with low nectar yield, even in the height of spring flow, and you have a recipe for starvation, disease and death. Due to the losses many beekeepers are needing to purchase bees this year. Add the ever increasing interest in backyard beekeeping, and there will most definitely be a shortage in supply. The take home message is: buy your bees now, plant as much pollinator-friendly plants as possible, and get serious about preparation for the new season.

Important factors to consider when buying bees

Untreated bees

If you interested in Natural Beekeeping and chemical-free hives, it is best to try and source your bees from breeders who do not chemically treat their bees, organic or otherwise. Most commercial bees are treated for varroa mites and will be less likely to have long-term survival with the transition to natural methods.

While treatment is the preferred method for most beekeepers, among natural beekeepers, there are strong arguments against biochemical treatment, citing a decline in the immune system of the honey bee as a primary negative side effect. If you want to learn more visit the Natural Beekeeping Trust.

As local as possible

Like any animal, honey bee colonies adapt to their bioregion. Bees that were raised in a warmer climate, such as the California Central Valley will have a harder time adjusting to cooler climates or harsh winters. That being said, I have had much success raising bees in the Sierra Foothills of California at 2,500 feet from packages of untreated bees sourced in Sonoma county, a warmer, coastal region much closer to sea level. Heartier races of bees such as Russians can also have more success moving to colder (or hotter) climates.

Do I need to select a specific race?

Most packages and nucs will be of a certain breed unless they have been cultivated from feral colonies (my favorite choice!). Breeding for strong genetics is one of the most interesting areas of research regarding health and survival of the species. For those who do not want to chemically treat their bees with miticides and antibiotics, breeding for strong genetics is the way to go.

There are a number of different bee stocks that have been bread for different qualities such as mild temperament, heartiness and productivity. Michael Bush has a great list of bee races here.

When purchasing bees, it is important to find out as much as possible about the bees you’re obtaining, including the race. Some beekeepers offer a choice between stocks. Italians for instance, are mild-tempered bees that thrive in Medditerean climates. Russians tend to be stronger and better for wintering over in cooler climates.

You can start with a specific breed, but remember that if the bees replace their old queen with a new one for any variety of reasons the new queen will openly mate with drones of various genetics and you will no longer have a hive of a singular race.

Four Ways to Obtain Bees

Package

A package is generally made up of 3-5 pounds of bees (about 10,000 bees) that have been shaken from hives into a small ventilated cage and supplied with feed. Most packages come with a queen in a small cage inside the package. Some bee suppliers (particularly those that ship by mail) sell the queen separately. Packages are best hived within the first 4 days after being shook unless conditions do not allow for it. The sooner the bees get into their hive, the more likely they are to survive.

It is important to understand that a package of bees is not a colony yet. They have no allegiance to their queen and they are often made up of unrelated bees.

Pros:

The easiest and most common way to attain bees.

Can be shipped from anywhere in the country (not always the best thing).

The most common way to buy bees for Top Bar and Warré hive styles.

They can start building natural comb right away.

There is no pre-existing plastic foundation in the hive.

They are less likely to be carrying mites, chemicals, pesticides, bee pathogens and other problems from their previous hive.

Cons:

These bees are often not sisters. The queen is not their mother and they all have to learn to adapt to each other and accept the new queen.

Sometimes they do not accept the queen. In these cases they ball and sting her to death preferring to raise their own queen. However, you may have to provide them with a new queen yourself. Pay attention in the first two weeks!

They are more at risk of starvation if you do not feed them enough. They came to you with no stores and nowhere to keep stores. They were not prepared for the forced move in the way a natural swarm is. They have to build all their comb from scratch and comb building takes a tremendous amount of energy (read: honey/nectar).

Nuc

A nuc is a nucleus colony of bees. The bees arrive in a small, ventilated box with a number of frames that can be placed directly into a waiting Langstroth hive. These frames are filled with capped brood, larva, honey, pollen, bees and a queen.

Pros:

Nucs are the most reliable source of bees out there, however they are predominately made for Langstroth hive.

The colony is stronger that a package because they have food stores, pollen stores and drawn comb.

Cons:

There are very few, if any, resources for Warré or Top Bar nucs. People who option for a nuc, but have a Top Bar hive often perform tricky comb cut-outs in order to fit the fragile nuc into a top-bar hive. This is not recommended for beginners.

The combs are usually built on plastic foundation. If you intend to use a Langstroth hive, I highly suggest turning it into a foundationless hive, which allows the bees to build natural comb. You will have to rotate out the old foundation comb over time.

Most nucs are assembled from old comb, which is dark brown from years of use. Old brood comb is more likely to contain chemicals from previous treatments, disease and pathogens. I suggest asking the beekeeper if they can provide bees grown on newer comb.

Swarms

Bee swarms occur in the spring and are the natural way a colony reproduces. In the winter, the colony clusters in a small tight ball, containing enough bees to survive, but not too many to eat through al the winter stores. In the spring, the queen begins laying again and the hive expands rapidly. If the colony feels strong enough to reproduce, they will begin to raise queen larva. Before the new queen is born, they will send the old queen out to find a new home. She is accompanied by anywhere from 1/3 to 1/2 the hive of worker bees in what is called a swarm. The bees will then cluster around the queen on a nearby tree branch, bush or anywhere that is convenient (like your roof gable!). The bees then send out scout bees to search for a new home. They will stay on the branch anywhere from 30 minutes to a number of days while looking for a dark cavity to call home.

A swarm in it’s first few days is very docile. They have eaten enough honey to last them about 4 days and are only interested in finding a home. While being around a swarm of bees can be intimidating, it’s one of the most incredible and gentle experiences you can have with bees. A swarm is a new being in it’s birthing process. It is delicate, vibrating and full of life. I have touched swarms with my bare hands, but don’t recommend this to beginners.

Catching a swarm is adventurous and exciting. It’s the cheapest way to obtain bees if you are willing to do it yourself. Many beekeepers also offer a swarm removal service and will sometimes sell you a caught swarm for less than the cost of a package of bees.

If you want to catch a swarm yourself try contacting your local beekeeping association and getting on the swarm call list. Be prepared for a call any day in the spring. You will have to drop everything and go!

Alternatively, you can join Honey Bee Allies and register as someone who either wants a swarm or is willing to collect/catch a swarm.

Pros:

It’s a natural birth! This is the most healthy way for bees to reproduce and helps to support a natural life cycle and thriving bee population. These ladies are ready to build comb fast. They are also not in shock from being shaken into a package or transferred into a nuc box.

The bees are all related.

Docile and fairly easy to catch, especially within first day or two of swarming.

Cheapest option for getting bees.

Do it yourself!

It’s Magical.

Cons:

There is no way to know if your swarm is made of strong bees or weak bees. The queen may be a weak, intercast queen or simply too old to produce enough healthy eggs. Pay attention in first two weeks!

Catching a swarm requires you to be available to drop everything and go. It’s free, but it costs your time, patience and flexibility.

A swarm sometimes rejects the new hive you’ve given them and may abscond. This is actually true for any new colony, no matter what, but more common with swarms.

Purchase a Pre-existing Colony

Sometimes beekeepers will have an entire colony for sale. This is a great way to become familiar with beekeeping, while avoiding all the risk of installing packages, swarms or nucs.

Pros:

Get access to a fully functioning hive from the beginning.

The bees may give you a swarm that same season, with which you could start a second hive.

Cons:

By far the most expensive way to obtain bees

Heavy to lift and move

May come with a host of pre-existing problems and diseases

The equipment and comb may be very old. It’s important to check the hive before you purchase it. Ask the beekeeper for a full history of the hive including if it’s had any chemical treatments.

Becoming a beekeeper is a wonderful journey. If you are serious about taking care of this new being you’ve decided to be responsible for, you will receive immeasurable benefits from the experience. The seasons will take on new meaning, plants suddenly become an exciting food source, you will develop an oddly obsessive relationship with fuzzy honey-makers, you will learn how be calm and move slowly with a humming, vibrating super-organism, you’ll spend time outside just watching the comings and goings, and maybe, in years to come, you’ll get a little honey.

However, becoming a beekeeper is no simple task. It takes time and willingness to truly dive in. You become a steward. You become a guardian.

If you are ready to take the next step, choose a hive design and get some bees I offer consultations here. There are also fantastic books and online resources. You can find an extensive list here. Enjoy the discovery!

A Walk Through an Herbalist's Garden

Melissa bends low and plucks a small herb growing out of the cobble stones in front of her house. She holds it up to the light and shows me the tiny perforated holes in the leaves.

“That’s how you can tell it’s the medicinal St. John’s Wort.”

Note: Melissa is a fictitious name to respect anonymity of person and place. The name 'Melissa' translates to 'honey bee'. No photos were taken on location.

Melissa bends low and plucks a small herb growing out of the cobble stones in front of her house. She holds it up to the light and shows me the tiny perforated holes in the leaves.

“That’s how you can tell it’s the medicinal St. John’s Wort.”

She presses the sample in between a card about the medicinal properties of St. John’s Wort and offers it to me.

Melissa is a licensed herbalist living in a serene tucked-away valley in Southwest England. Her practice and gardens sit on one side of a happily meandering river, and on the other, there are two hives of bees. We stand in the early morning sunlight, watching the bees from the opposite side of the river. I don’t have to ask to know we wont be going any closer. These bees are to be left undisturbed. They are part of the land, as much as the hazels and the stones. Melissa regards them with an appraised respect. She never goes into the hives, and clearly does not keep bees for the purpose of harvesting and selling honey. The bees are part of the land and the land is rich with the plants that heal. They are wild hives.

Melissa takes us past the historical stone building on the property and into her gardens. She is wearing sturdy trousers, wellies and a thick wool sweater with a leather tool belt strapped around her waist where she can store her clippers and garden shears. She is every inch the embodiment of wise, practical and earth-centered. When we contacted her to find out if we could meet, she expressed that to visit is really about visiting the land, and since she lives on the land, she is more an aspect of the land itself.

After the bees, Melissa takes us by her wild garden. Once again, she doesn’t explain much, other than it is wild. I am reminded of a saying I once heard. “Always leave a part of your garden wild for the fairies." In this case, I think the fairies are the spirit of the land itself, the devas of the trees and river, made manifest in freely growing flowers and medicinals. It is a sage practice in that it honors both yourself as steward of place, and the land in its wild, infinite wisdom.

We pass through a bower and along the circuitous “rows” of her cultivated herb garden. I see carpeted thyme, raspberry, lavender and hawthorne. There are apple trees endemic to the valley, so old I feel like bowing to them. She teaches us the best way to pick apples and we harvest a pile of “cookers” and a pile of “eaters” to take home.

“You know an apple is ready to pick if your twist it, ever-so-gently, and it comes away. Never pull it.”

Inside her workshop, the light is dim, creating an immediately hushed, cosy environment. Here we find the transformation of her labors with the land into herbal medicines. On the table illuminated by a shaft of filtered light, is a large round basket of drying nettles. Nearby sits another basket fill with some kind of root, and above, herbs drying in bunches. Along the walls are bags and bags of neatly arrange herbs, and in the corner, there is a hearth with a kettle. Only in my dreams have I ever seen such a place. It is at once ancient and modern. I feel awed by the complexity of knowledge Melissa clearly possesses, while at the same time, comforted by the simplicity of being with the plants.

When speaking to her, I feel as though I am speaking to the voice of the valley. There is a deep listening in her presence that found often among those who live close to the earth. A listening that is more difficult to cultivate in our urban, technology-driven lives, but still possible. To listen deeply is to see true.

As someone who is currently not rooted to any one place, and is ultimately seeking a home (even if it’s more than one home in more than one country!), I find myself thinking about what it means to be truly rooted to a piece of land. I am lucky to travel the world and fall in love with landscape, people, cities and communities everywhere. I root myself in the act of being as present as I possibly can wherever I am. I am by no means a master as such things; that’s why it’s called a practice. In doing so, there are certain landscapes, just like certain people, that our bodies resonate to. Place where we receive an internal yes that has very little to do with the mind, and everything to do with the land. Earth reaching up as the body reaches down. How must it feel to know one piece of land so intimately that each flower, each root, each passing of the seasons becomes an extension of the self? The self becomes a reflection of the land: moulded, tempered and transformed.

I leave you with this quote by John Seymour, author and pioneer in self-sufficiency and environmental awareness:

“The ‘owner’ of a piece of land has an enormous responsibility, whether the piece is large or small. The very word ‘owner’ is a misnomer when applied to land. The robin that hops about your garden, and the worms that he hunts, are, in their own terms, just as much ‘owners’ of the land they occupy as you are. ‘Trustee’ would be a better word. Anyone who comes into possession, in human terms, of a piece of land, should look upon himself or herself as the trustee of that piece of land - the ‘husbandman’ - responsible for increasing the sum of things living on that land, holding the land just as much for the benefit of the robin, the wren and the earthworm, even the bacteria in the soil, as for himself.”

Beautiful Homes for Ladies and Bees

Sometimes it's important to take a moment to simply appreciate beauty. Physical beauty. Beauty of nature. Beauty of place. Beauty of soul. I've been thinking a lot about beauty lately. Beauty as a power that evokes a sense of peace, wonder and love.

Sometimes it's important to take a moment to simply appreciate beauty. Physical beauty. Beauty of nature. Beauty of place. Beauty of soul. I've been thinking a lot about beauty lately. Beauty as a power that evokes a sense of peace, wonder and love. Beauty that comes from the natural world and is emulated time and again by art. Whenever I travel to places that have architecture older than the birth of my country, I am wistfully awed by the detail and artistry found in everything "old". The artistry found in homes, gardens, cathedrals, temples and pieces of furniture.

Beauty moves us. It inspires us. It is a powerful agent of spirit, and we are drawn to it in it's exterior and interior forms. This post is a nod to the human capacity to create art and beauty through the form of a home and a hive.

These photographs are of a home I had the luxury to visit after completing my workshop in Bath. I spent a glorious afternoon and evening, surrounded by many bee sisters, soaking up the beauty of place, kinship, healthy food and deep rest. I am aware of the privilege of this experience, or the privilege to travel the world for please in the first place. I am aware of how many people are in incredible suffering while I write a post about a beautiful home. I often come up again this conundrum when appreciating beauty that comes from affluence. How can we appreciate or have privilege and luxury while remaining in service to creating a world with greater equality and less consumption? I don't have an easy answer, other to be fully present with where I am, feast or famine. If I am offered a room with a mural, a dip in a private pool and the most generous of meals by a kind sister, I will be in gratitude, I will ask myself to relax, I will be in my heart.

There is no better teacher for this kind of presence than nature. She, the Earth, the natural world, has a beauty, a wildness, that has captured the mind and imagination of artists and biologists alike. The incredible perfection of life-sustaining forces that create mathematically complex growth and movement patterns such as the spiral of a sunflower's seeds, the orbits of the planets or the hex of the honeycomb. Across many ancient and indigenous cultures, this interior world of the hive is one of the most highly regarded examples of nature's mysterious, divine beauty. Glyphs and art depicting the human reverence for the honey bee are found as far back as ancient Egypt and Sumer.

Have you ever seen the inside of a hive? Watched the bees move across comb? Been mesmerized by the coming and going of pollen-bearing, sun-glowing insects. And have you ever notices how this incredible beauty is so disregarded by the form and mechanized construct of the conventional bee hive. Langstroth hives, the white boxes you see lining desolate orchards in drought-stricken California for stark example, were built for humans in order to maximize honey production. They have very little to do with what is most beneficial for the honey bee colony. I'm not unequivocally against Langstroth hives. There are plenty of bee-sensitive beekeepers out there who use langstroth hives. If you go to a bee supply shop, you'll find supplies for a Langstroth, but you likely wont find top bar hives, log hives, golden ratio hives or Warré hives (unless you go to Bee Thinking in Portland!). I'll get into my pro's and con's, feels and theories about lang hives another time, but for now, lets just say, I've tried them out and we didn't become best buds.

There are so many hive styles out there, ranging from log hives found in trees (see Michael Thiele's work with log hives), to sun hives, to strange walled contraptions that are supposed to offer high-rise indoor observational viewing (iffy choice). I encourage anyone interested in getting bees to look into some of the back-to-nature, DIY hive styles out there. Alternatively, you can build or buy a Warré or Kenyan Top Bar hive - two top bar style hives that are relatively well known. Note: I'm not getting into the British national hives because it's not quite as well known in the states and I don't have enough knowledge.

Combining art and hive style, more and more beekeepers are getting into beautifying the exterior of their hives, and why not? We see such incredible beauty in nature's own work, why not show the reverence of the interior temple of the hive through our artistic additions to the exterior? If you decide to put your bees in a box (as opposed to a skep or log) and become responsible for them, why not let it be a box of personal artistry? Painted, carved, designed, and placed in a beautiful space - let your creativity come through.

Perhaps through this artistic weave between the human world and the non-human we can all find moments of presence with the beauty that is Spirit in form.

An Apiary in the Hedgerows

Angharad has just returned from a walk with a handful of blackberries, elderflowers, nettle and apple. She is going to make a fruit crisp and some tea. Three things about this:

1) Angharad wildcrafts like some people (me) frequent cafes; It’s a nonchalant, every-day sort of thing.

Angharad has just returned from a walk with a handful of blackberries, elderflowers, nettle and apple. She is going to make a fruit crisp and some tea. Three things about this:

1) Angharad wildcrafts like some people (me) frequent cafes; It’s a nonchalant, every-day sort of thing.

2) She doesn’t have to do so with the fear that someone will run her off with the right to bear arms and an angry dog. Novelty.

3) She found bee hives.

An apiary to be exact. The next farm over, near some old rows of sunflowers and leeks.

But first things first. Angharad is one of my English bee sisters. I’ll be saying 'Bee Sister' from time to time, so to be clear, a bee sister is a kindred spirit, Woman of the Bee, and usually also a woman whom I have studied with in England regarding old folk traditions to do with honey bees. I am staying in a terribly adorable cottage with Angharad and two other American bee sisters while we attend a workshop in Bath.

Angharad is an artist from Devon, a woman of the moors, and a fantastic maker of “worthy” foods: a Devon slang (she says) for particularly extra healthy foods that go well beyond “crunchy granola”, into the realm of hand-ground grains and self-harvested seeds. Naturally, she found us an autumnal feast of berries. You can find her art here.

The bee yard she discovered is a colorful haphazard apiary tucked in a circle of evergreens. The boxes are in different states of age and disrepair, brightly painted and oriented outwards. Tools and comb carcasses like about, and the bees feel a bit on edge, but healthy nonetheless. This beekeeper treats the bees. There are bottles of chemical treatments on the grass. There is also a hungry, nasty nest of wasp, ever-hunting the weaker colonies. I imagine this is why the bees feel a bit on edge.

Wasp are a big problem for honey bee colonies in England. Most beekeepers I’ve spoken with are used to loosing hives from wasps the same way American beekeepers talk about varroa mites (although England has varroa as well). In the summer, many beekeepers reduced the entrance to their hive to bee size: just big enough to allow one or two bees to pass through, and allowing guard bees a smaller territory to defend. Once a wasp gains entry to a hive, it will eat brood, honey and kill bees. If it makes it out of the hive alive, it is covered with the scent of the hive and the guard bees allow it back in, not realizing it is an imposter. Entire colonies are taken down in this way. You can imagine why this apiary may have been a bit more on edge.

There is something so liberating about walking the english countryside. While I’m sure the local farmer wouldn’t exactly love us ladies visiting his/her hives, the fact that they are just simply there, up the track without a fence, a “keep out,” or a “beware of bees” sign, softens my heart. This is a country made of up footpaths and hill walking. I feel simply elated when I see another Public Footpath sign jutting out from the hedgerow. Like I’m getting away with something every time I pick an apple or strike out across of field scattering timid sheep. If you pass someone on a walk in the countryside, you always say hello. It’s neighborly and civil. I love it.