A crown of Ivy

It happens every year. I am on a walk on a warm fall day in November. The kind of day where you start your walk with a hat and a sweater and end your walk in a t-shirt. It’s always the sound that catches my attention. So late in the season, it’s unusual to hear the loud hum of many foraging bees.

Ivy (Hedera Helix)

ifig • efeu • eidheann

Hedera - from Proto-Indo-European meaning “to seize, grasp, take”

Helix - Ancient Greek to “twist, turn”

Main Pollinators: Honey bees, ivy bees, bumble bees, butterflies

Pollen color: Yellow

It happens every year. I am on a walk on a warm fall day in November. The kind of day where you start your walk with a hat and a sweater and end your walk in a t-shirt. It’s always the sound that catches my attention. So late in the season, it’s unusual to hear the loud hum of many foraging bees. Especially when that hum is coming from above you. The bees are foraging on the late winter bloomer: creeping ivy. You know, the kind of ivy that curls up redwood trees or along the brick of old houses? Ivy is found in most of North America, Europe, North Africa and Asia. It spends it’s first 8-10 years focusing on growth, and then turns it’s attention toward flowering.

Ivy Bees in England

I bet you’ve never even noticed the ivy flowers, but the bees sure have. Ivy is a key resource for autumn-foraging bees. While it does provide pollen for many pollinators, honey bees are mainly after the nectar. Ivy honey sets very quickly. Once set, it looks more like crystallized fondant than honey. Bees use this honey as an important food source in the cold winter months. To do so, they have to mix the ivy honey crystals with water to dissolved them enough to be digestible. Humans also harvest and sell ivy honey. To do this they have to slowly warm the honey, being careful not to melt the wax. it’s a tricky process and must be done with utmost care, as to not steal the last of winter stores from the bees.

Ferdinand Leeke

Ivy sometimes gets a bit of a bad wrap. It’s annoying to gardeners and often associated with darkness and “creepy” places such as graveyards. In truth, like other powerfully medicinal plants (seriously, ivy honey is so good for you), ivy has a long history as a plant sacred to the gods. In Celtic lands, Ivy is often associated with the tree alphabet letter “Gort” and carries the serpentine wisdom of transformation within its twisting vines. Throughout Celtic myth and folklore, ivy can be found at the doorway between this world and the fairy kingdom. This is no small thing. The fairy kingdom was more than a place of fancy, it was and is the Celtic Otherworld: a land of mystery, magic and spirit. Ivy marks the doorways where the veil between this world and the world of spirit is thin. They are places to seek wisdom, but also be cautious of, for encounters with spirit can be quite altering.

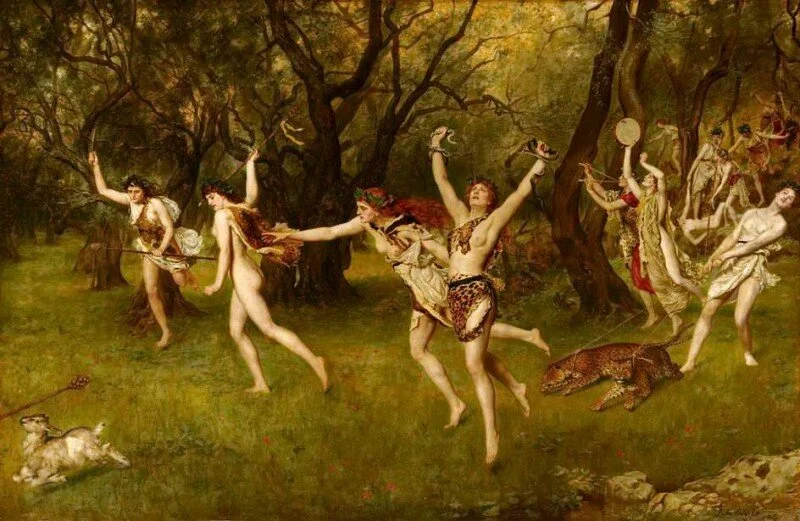

Ivy is also famously sacred to the god of intoxication, wine and pleasure: Dionysus. Similar to Zeus, who was secreted away and raised on honey by nymphs, the infant Dionysus was hidden from Hera and raised by Nysiades (nymphs) in the ivy-thick woodlands. It is said he was bathed in the spring of Cissusa, meaning “Of the Ivy”, where the waters sparkled like wine and tasted as pleasant. His nymphs and priestesses carried staves entwined with ivy. Dionysus himself wore a crown of ivy, which was meant to protect and guide the experience of intoxication, so that the drinker may only experience the positive benefits of the wine. While Dionysus is commonly associated with drunken revelry, his cult rituals ran much deeper than that. Intoxication does not only come from a heavy night of drinking. One can be intoxicated with spirit and enter a euphoric state. Ivy was not simply a plant of protection, but also a euphoric plant of prophecy. The nymphs/priestesses of Dionysus, known as maenads, were said to be as intoxicated by ivy as they were by wine. It is interesting to note that Ancient Greek brides often carried ivy at their weddings, symbolizing fertility, fidelity and union made in love.

As with most symbols of power, we find a reoccurring theme of polarities. Ivy is associated with death and transformation as well as evergreen life and fertility. It carried both the intoxicant and the sobering effect. It is the twining, serpentine feminine around the sturdy oak and holly king. It guardians the Otherworld and bears it’s nectar to the honey bee, she who fluidly flies between the world of the living and the world of the dead. It brings the transformative powers of deeply altered states and it binds and entwines through the commitment to love.

John Collier - Maenads

The Big Bad Varroa Ally

This morning I sat in a garden teaming with the birds and the bees. Humming birds noisily darted between creeping vines of nasturtiums, red raspberries hung plump and inviting from semi-orderly thickets, honeybees swooned in the fuzzy clumps of borage, and zucchini’s performed their summer competition for Most Alarmingly Large Vegetable.

This morning I sat in a garden teaming with the birds and the bees. Humming birds noisily darted between creeping vines of nasturtiums, red raspberries hung plump and inviting from semi-orderly thickets, honeybees swooned in the fuzzy clumps of borage, and zucchini’s performed their summer competition for Most Alarmingly Large Vegetable. I was at Wildflour Bakery, a jewel of fresh baked bread and Goat Rock Roast Coffee a lazy drive down Bodega Highway. While it does have it’s downside (read: Optionitis for those who dare to choose only one loaf), it’s a not-so-secret favorite secret spot in my new home of Sebastopol, California.

I nestled myself into a garden bench with a Butternut Squash and Gouda scone and proceeded to read a most unpleasant article, but thought provoking article.

The article was titled "The Colony-Killing Mistake Backyard Beekeepers Are Making”. Let’s start there. I steer away from articles that promote fear and shame on the outset. This type of headline is mean to make you worry before you even click on the link. However, a natural beekeeper once told me that she does her damnedest to stay abreast of the conversation. She reads new research, seeks varying opinions and strives to be as educated as possible, so that when she faces a room of conventional beekeepers and states that she doesn’t use treatments and her hives are thriving, she can back the guffaws and protests of the impossible with observation and research-based knowledge.

My morning read didn't have a lot of meaty substance to it, but the thing got me thinking. It was one of the many articles I’ve seen admonishing backyard beekeepers for refusing to treat their hives with chemicals, organic or other. It speaks to the dangers of allowing mite populations to flourish, infecting other colonies for miles around and putting the species at risk. It speak to a desire that every backyard beekeeper at the least, consider chemical treatments. Miticides are, as we know, the tried and true, scientifically studied method for saving the bees.

In a video by the Rucher Ecole, treatment-free beekeeper David Heaf states “putting chemicals in the hive doesn’t just contaminate your hive products. The honeybee is susceptible to some of the miticides....It’s just trade-off against the damage to the bee and the damage to the mite….But worse still, because some of these actors are kinds of antiseptic, they seriously disrupt the microbiological environment in the hive. Bees hugely depend on the other organisms, the microorganisms in the hive, for a healthy ecology of their hive, for the health of their young and the health of themselves."

Despite such encouragement toward treatment-free beekeeping, I used to struggle with what to do. I used to ring my fingers over whether or not I should get on board and just treat my bees. I used to ask myself if not treating my bees was a form of torture. I asked this because a highly regarded local beekeeping authority from my home town of Nevada City, CA told me it WAS a form of torture. He told me the people from Marin and Sonoma who practice Natural Beekeeping were “The Taliban of Beekeepers”. Needless to say, I never went back to another one of his classes.

I began to seek out other kinds of beekeepers. I found people like Corwin Bell, Heidi Herrmann, Gunther Hauk, Michael Thiele and Jacqueline Freeman. I went looking for those “terrorist” beekeepers the man in Nevada City so aggressively disliked. I found places like The Melissa Garden in Healdsberg, CA and The Natural Beekeeping Trust in England. I started to find my kindred spirits of the bee world. Bee Guardians who have raised bees without chemicals or antibiotics. People who had, against all mainstream belief, manage to raise healthy, lasting colonies. Honey bees that even co-exists with varroa.

What are they doing different? Why do their bees thrive, despite the odds? While each natural beekeeper’s practices are different, I began to notice certain commonalities (generalizing here): they allow swarming, breed strong genetics, talk to their hives, adopt alternative hive styles, harvest much less honey (if any), plant for pollinators, rid their gardens (and neighborhoods) of pesticide use, don’t feed bees sugar, and keep their bees in one place. In short, they listen to nature. They listen to the bees.

What I find again and again, is the health of the colony or apiary is directly related to the health of its environment. Humans and bees are not so very different. Our health suffers in emotionally, physically, mentally or spiritually stressful environments. The very foundations of conventional beekeeping practices are part of what is harming our bees. I’m not a scientist, I don’t have proof. I am one of the billions of lifeforms, who’s shared birthright is this planet, who can feel the places we are out of balance and seeks to right that balance by listening to the Earth.

If that’s a little to loose for you, try this: pesticides actually do kill (they are design to) and if you want healthy bees start by eradicating pesticide use from your seeds, your garden, your neighborhood, your country, your planet.

Returning to my morning garden moment, as if on point, in my caffeine-induced, bee-advocate reverie, I heard a British woman exclaim, “There are just so many bees here! I love the bees! Isn’t there a kind of pesticide that’s hurting them?” Without thinking, I shouted through a patch of sunflowers, “Neonics! I mean, yes, there is. Sorry! Didn’t meant to interrupt. I’m a beekeeper. They’re called neonicotinoids.” She looked at me blankly, after which, I thoroughly retreated back into my unassuming bench, and read on.

There was one more particularly crunch paragraph in the article that caught my eye. "Bees face other challenges beyond mites, including poor nutrition, disease and pesticides. Even veteran beekeepers say it takes more effort to keep their bees alive these days.”

I had a little chuckle to myself. Yup, other challenges. It comes back to our very Western way of thinking: treat the symptom not the cause. Varroa is a symptom of a much larger dis-ease in our pollinator communities. What if, instead of looking at Varroa as a monster, we looked to Varroa as an ally? The dark shadow-self that comes forward when we need to look at something we have been unwilling to see? An aspect of the entire ecosystem that has it’s place in the larger story. Some piece of our own wholeness that has gone out of balance and “appears” as a demon (ok ok, a mite), but is really just a way our inherent wisdom is communicating with us. I know I’m making metaphors between the human psyche and beekeeping. Just be cool with it. I’m a beginner. I know a whole lot about bees and will probably never stop being a beginner. This is the way of learning the natural world.

The truth is, when it comes to beekeeping, colonies that come from treated parent colonies are going to have a really hard time making it through without treatments. These are bees that come from packages and nucs sourced from large-scale conventional beekeeping operations after the hives have traveled to the California almond pollination event in early spring. They are often not coming from a healthy environment, have been fed sugar, and are of weaker genetics than naturally raised or feral hives. As a beekeeper helping other backyard beekeepers get started, this question of source is ever-pressing. How do I help bees coming from treated colonies make the transition to treatment-free beekeeping? I wish we could all set up apiaries and naturally breed our own strong colonies, but alas, there are still too few beekeepers trying things the old old old school way. I will keep asking this question, because I believe in backyard beekeeping, and I believe it can do much more good than harm.

In the mean time, grow your gardens without pesticides, plant for pollinators, educated yourself, and sit next to your hive. Grab a cup of tea and sit there a long time. Sit there until the Mad Woman of the House goes quiet inside. Sit there until the life-hum whispers a sweet honeyed language into your heart. Sit there until you are bored. Sit there until you realize, without noticing, a great calm has descended upon you. Sit and talk to your bees, for I promise, with absolutely zero science to back me up, they will most certainly talk to you.