For the Love of a Tree

I remember when I first read the Holy Thorn tree had been cut down in an act of vandalism. I cried out and burst into tears. I was at my parents home and was crying too inconsolably to tell them what was wrong. I was acting like someone had died. In many ways, someone had.

I remember when I first read the Holy Thorn tree had been cut down in an act of vandalism. I cried out and burst into tears. I was at my parents home and was crying too inconsolably to tell them what was wrong. I was acting like someone had died. In many ways, someone had.

We can wax poetic about how we’re all interconnected, but the true sense of kinship and belonging to this Earth happens in relationships. A relationship to one beach, one particular herb, one particular tree. Relationships that go beyond imagining the tree has a spirit, to the simple feeling of “this tree is my friend.”

I get so overwhelmed with existential grief around what’s happening to our planet, but there’s no healing when it’s that far out of our scope of relating. When the grief is for one place, one being, one spirit or group of spirits lost, then there is movement, catharsis, and possibly resonant change. When we feel feel the grief of lost relationships, we begin to understand just how tied we are to the more-than-human world. Sometimes we learn of our belonging through our loss.

I have made pilgrimages to Wearyall hill and the Glastonbury Thorn since I was 17. I knew this tree well. I have given it many offering, tied many wishes to its protective ring. The Holy Thorn was a wishing tree, a blessing tree. Across Celtic nations, there is an old tradition of tying cloth to sacred trees, both standing alone, or near sacred wells. The cloths are often wishes or prayers for healing, health, or good fortune. This tree, in particular, was connected to a local legend that claims Joseph of Arimathea visited this sacred hill, while carrying the Holy Grail into hiding. For some, this is the Grail of King Arthur’s legends, and they say the Once and Future king himself is buried in the local Abbey grounds. They also say this is where the mists parted and the priestess isle of Avalon was revealed in Arthur’s final journey beyond the veil.

The Grail Joseph of Arimathea was said to carry, is also though to have been Mary Magdelene herself, as well as the children she bore with Jesus, as the grail is considered symbolic of the Magdelene line and essence. There is even a telling that Joseph of Arimathea brought a 12 year old Jesus to Glastonbury during one of his trade missions. The tree represents Joseph’s staff, which he planted upon arrival to Wearyall hill.

This land is full of myth and legend. What I share only scratches the surface of the confluence of myths living in the landscape.

This tree too on a deeply symbolic meaning to me, but it was also a tree I came to know as friend over the years.

It was both a symbol of the greater mysteries of the sacred, as well as a point of reference. A place where I could tangibly feel the meeting of the worlds: nature and human, magical and mundane, this world and the otherworld. It was a place both solid and liminal at the same time. Many prayers of mine were given to that tree. Many have been answered.

I think in our quest to reunite with ourselves as relational members of the more-than-human world, we have to remember that it starts with individual relationships. It starts with love affairs. These can be near and far. A moment with a sea turtle in an underwater queendom. A conversation with a rock in a desert. A friendly swell of the heart when seeing a favorite creek spot. A deep sigh when gazing on a familiar mountain. Who have you befriended in this wide, wonderful earth? Which cave, tree, cactus, or meadow calls you kin? Calls you home to your own belonging?

The 3 first photos are of the intact tree in 2013. The last is 2015, after it was killed.

You are the Bridge

Where did it begin? This love affair? This obsession? This reverence? Was it in our prehistoric ancestors, with fire in their hands, climbing the highest of heights to gain your nectar? Was it in the way your honey and pollen aided in the development of our ancient brains?

Where did it begin? This love affair? This obsession? This reverence? Was it in our prehistoric ancestors, with fire in their hands, climbing the highest of heights to gain your nectar? Was it in the way your honey and pollen aided in the development of our ancient brains?

Did it begin with those first altars of honey? With those myths of rivers filled with honey wine? With a white she-goat dripping mead? With the tree whose sap means honey and whose promise is life?

There is no tracing the origin of our courtship with the bee. Only honeyroads to follow into and out of antiquity. See the bee nymphs, dusted in pollen, who whispered the art of prophecy to the sun god. See the tears of Ra who fell to the earth and became bees. Christ's tears as well. Hear the hum on the lips of poets. Trace the sisterhood in asterisms. Taste the food of the gods. What about when we wised up? Got rid of all this pagan polytheism? Forgot the Queen of Heaven and chose one god. Did our obsession end? We took Her out of the picture, but did our fascination cease? Ask the priests who brought hives to the new world, because no Catholic mass could be held without holy beeswax candles. Ask the Christian family who brought cake to the bees after Christmas Eve mass. Ask the men of industry and innovation who sought to find a way to better manage this nest of divine beauty. Were they any less mesmerised than Aristotle? Hafiz? King Solomon?

Where has it gone to? This love affair?

Into the many rivers of the inquisitive religion of the modern era: science. That beautiful achievement of the honed intellect. Science, who's “authority has grown so immense over the centuries that it now claims supremacy over all other forms of thought.” (William J. Broad). A gift, this science. And a limitation, if it excludes the old memory of body, poetry, spirit and the ineffable.

What comes next in this love affair? What does the reawakened feminine bringing to the conversation? What happens when we weave centuries of honeyed wisdom with centuries of scientific progress. What else is possible? You are the bridge.

Respecting the Sovereignty of a Body

Happy Friday the 13th, a day long associated with women’s bodies and women’s cycles. Did you know that a woman has her moon cycle about 13 times a year?

Happy Friday the 13th, a day long associated with women’s bodies and women’s cycles. Did you know that a woman has her moon cycle about 13 times a year? Funny how a number associated with women’s potency, power, magnetism and fertility was conveniently turned into an “evil” number.⠀

⠀

As we do the incredibly tenacious work of teaching the world to honour women’s bodies, we are doing so much more than supporting female bodied humans. There is a direct line from subjection and abuse of women’s bodies to the abuses done to the Earth and it’s creatures. With the advent of Patriarchy, the act of imposing power over a woman’s body led to the skewed world view of man’s dominion over the Earth rather than partnership and stewardship with the Earth. The inherent fecundity of the Earth has long been associated with woman and the power of the womb. Despite ages of misogyny, the Earth is still called Mother Earth. Even after the arrival of Patriarchy, there continued long-held beliefs associated with the Goddess of the land. In Celtic nations, to earn governance of the land, the King had to wed the land, known as Sovereignty. It was only she who bestowed sovereignty upon him. ⠀

⠀

The suppression of a woman’s voice, the denial of climate change, and modern day beekeeping practices are all related. They all source from a belief system that is both threatened by and in direct opposition of the sovereignty of the body. When we started placing more power in the As Above, ignoring the So Below, we forgot our own birthright as beings woven into the fabric of life. One of the most radical things you can do to disrupt the broken system of our times is to listen to the body. Yours, the bees, your children’s, your beloved’s, the Earth’s.⠀

You want to be a beekeeper? Start with hearing and respecting the inmate language of your body.

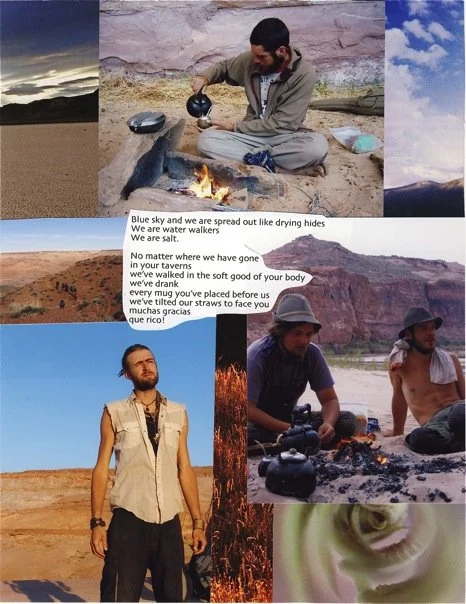

Shamanism Meets Tea Time

I’m about to board another flight to London. I seriously can not wait for scones and tea at No. 9 on the Green in Wimborne. I am visualizing pouring cream into a saucer as I write. Heaven.

I’m about to board another flight to London. I seriously can not wait for scones and tea at No. 9 on the Green in Wimborne. I am visualizing pouring cream into a saucer as I write. Heaven.

I have a suitcase filled with long skirts, a wooden distaff, special rocks, wellies, and an air purifier. Not the most obvious choices for a trip to England. Ok, the wellies get a pass, but they’re so damn heavy and awkward. (Please don’t tell me to wear my weight on the plane. You ever try wearing knee high rubber boots 7 miles over the ocean?) I’m on my way to the Sacred Trust, a school for shamanism, deeply rooted in the Path of Pollen, a European shamanic tradition with the honey bee at its heart. The air purifier is just because I’m allergic to mold. Go figure.

People have started to ask me if I live part time in Europe. I’d LOVE to say Yes, but the answer is, not yet. Since 2010 I have been traveling to the Sacred Trust to study a form of shamanism that survived the Romans, the Dark Ages, and the Inquisition. I equate it to a graduate program. A big investment with my time and money, which is helping improve my mind, body, heart, career and life path. That’s how I justify it to my left brain. My right brain couldn’t give two effs, because this work is 600% soul food.

The school teaches a line of gynocentric, bee-centric shamanism that honors the feminine principal. It is mostly made up of female students, although there are many men starting to take newly offered classes for all genders. It mostly works with bees, but there are serpents, stags and spiders woven in. It is multidimensional and embraces the betwixt and between.

The tradition is a small golden thread. A quiet hum that lasted through the burning of our grandmother’s grandmothers. It’s an answer to my American hunger for spiritual belonging. A hunger that longs for a sense of spiritual roots, but wars with how to be a native Californian without appropriating the spiritual traditions of the Indigenous people of this land. I can not begin to describe the relief I felt when my heart encountered the bee tradition and I cried those soul-aching tears of recognition, knowing that somehow, not all had been lost.

Let’s unpack that for a moment. First and foremost, I need to address privilege. I’m a white, western woman. My ancestors are oppressors and I carry that in my lineage. I refuse to be blind to my own privilege, and as a result of that refusal, I keep discovering ways that I have been. Let me just state that I am learning and I have a long way to go. Also, I fly over an ocean 1-3 times a year in the pursuit of earth-based wisdom connected to the part of my ancestry that was oppressed by Patriarchy and Christianity. So while I resist the dominant social institutions of the former two powerhouses, I am also partaking in the hypocrisy of the entire capitalist, planet-degrading #deathspiral, by using fossil fuels to catapult me in a metal box to a place where I can feel connected to the earth. That’s some real bullshit right there.

Yet, I also subscribe to the idea that there are certain soul places on this earth. Certain spots that speaks to us. Speak through us. Calls us. Awakens us. Claim us. Can a person be OF their native soil and also OF a patch of earth 6,000 miles from where they first touched their feet to the dirt? I most certainly have been claimed by more than one place in my life. Just are sure as I have been claimed by more than one heart. The English countryside is one of those places. And it requires a good set of wellies.

On with further unpacking. When I say I cried because “not all had been lost”, I mean, I am woman and a member of the gender(s) who were and continue to be shamed, maligned, violated and abused for our sex/identity. The wisdom ways of women and the honoring of the feminine in earth-based traditions were nearly snuffed out in Europe’s long history of violence against the life-bearers. Coming to a tradition rooted in my ancestor’s homeland that honors the voice of the womb and the power of the feminine principal is cathartic, to say the least. We ascribe voices to various body parts all the time, but when was the last time you considered the womb to have a voice? Not just the heart, or the head or the phallus, but the womb? Think about it.

Now imagine if you found a place tucked between meadow and forest where you were encouraged speak with that voice. Dance with that voice. See with those eyes. Utter with that yonic intelligence. Imagine relearning your body as though it were flowing with nektars, like a flower. Imagine learning new tongues informed by wind, sea, honey and fire. For those of you who have been wondering why my feed is periodically filled with photos of tea and cobblestones, that is why.

What is The Path of Pollen? I can’t really answer that. It is indefinitely ancient and ever new. It’s part of a very old story. It’s part of writing a new story. Its fingers are made of threads, its head made of stars, its womb made of bees, its longing made of serpents entwined. It is wombic. It is phallic. It is Both And. It is Neither Nor.

I am part of a tradition that stretches its storylines back through the distaff path of ancient Europe. It is a tradition of bee women, known as Melissae, and is very much alive and well in the modern world. The Melissae were the bee priestesses of ancient Greece, most commonly connected to the oracular Temple of Delphi. The Delphic Oracle, also called the Delphic Bee or Pythia (pythoness), was the prophetess for the Earth and of the Earth. It is said the priestesses inhaled the breath of the Dragoness, Python, Gaia’s daughter, and entered a trance, uttering prophecy for all who came to the temple.

I am here to remember how to listen to the voice of the earth, as she arises, a buzz, from within. Ten thousand bees offering nectar on the breath of python. May I be so lucky to glimpse her in the mirror.

And I’m here for tea, scones and whisky, because I’m multidimensional AF.

Stalking the Wild Feminine

It’s going to be hot out there. No-option-but-naked kind of hot. Snake weather.

The bees will be gathering water from the banks of the Eel. The water ouzel will be dancing her grey-winged hop up and down the river. The bears wont come near. There are too many of us.

It’s going to be hot out there. No-option-but-naked kind of hot. Snake weather.

The bees will be gathering water from the banks of the Eel. The water ouzel will be dancing her grey-winged hop up and down the river. The bears wont come near. There are too many of us.

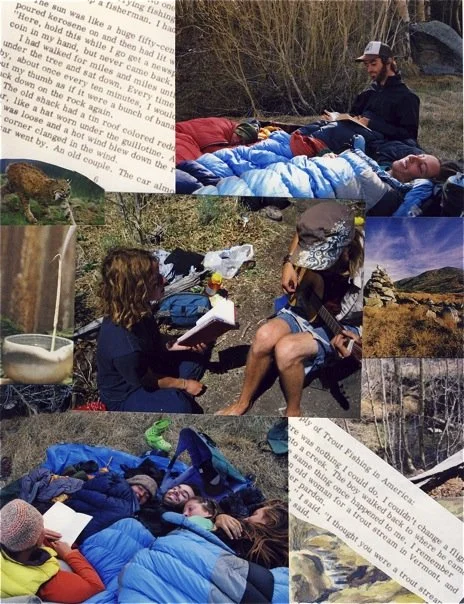

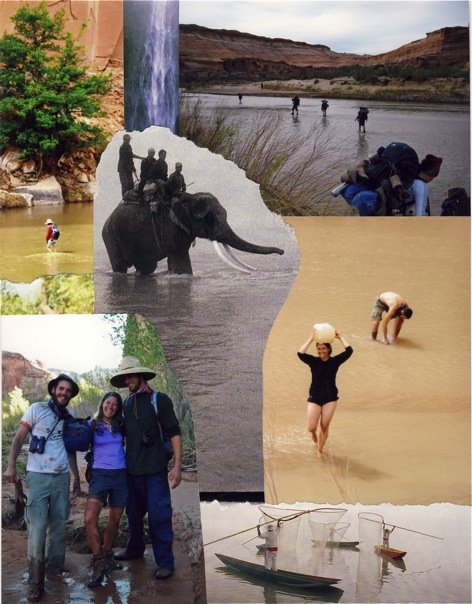

Tomorrow I’m going backpacking with thirteen dear friends. A reunion in the California wilderness. Ten years ago, we piled our bright eyes and burgeoning adulthood into a few likely-to-fail vehicles and set out on a four and a half month journey into the wilderness. I wouldn’t exactly call is a backpacking trip; it was less hike-through and more wilderness emersion. Alumni and friends of the Sierra Institute program, we went to learn about ourselves from the wilds and each other.

Three weeks fishing in the Marble Mountains, two weeks tucked under dripping canyon alcoves on the Dirty Devil river, three weeks following the creek lines through the frosty Whites, five days with grandmothers and ceremony in the Sonoran desert, twelve days vision fasting on the Kaibab Plateau with the School of Lost Boarders, a week along the sea battered edges of the Sinkyone. We sat in council, we ate wild watercress and wood sorrel, someone got lost for three days, people shared backcountry romance, people got sick, people got fed up and left, we disagreed, we laughed, we read stories aloud, wrote songs, met bears, wiggled into backcountry skin, made amends with our nature-starved souls, and broke ourselves against modern society.

We’re going back now. Thirteen busy adults with busy lives, affording ourselves four days to pay homage to four months of life altering earth-speak. For me this means snakes. Rattlesnakes. I find it a terrible irony that my favorite place in the wilderness is also one of the most snakey out there. To further the cosmic joke, I was born for wild places, yet life offered me a highly traumatic early childhood experience with death and a rattlesnake. Fast forward through twenty years of snake nightmares and debilitating phobia, and you find me dawning a heavy pack, hyperventilating in an Arizona parking lot, and hoofing it into the snake-rich springtime desert. I would not be defeated by phobia. I would stalk the wild feminine and surely and she stalks me.

Now, I am versed in venom. A woman of the bee, stung time and again. Since that journey, when I came face to face with my nightmare pursuer, I have negotiated a new relationship with bite and sting. I am not less afraid, but I less crippled. I am more whole. It has something to do with learning the language of dreams. With learning to read the story differently. Why does the serpent bite me, pursue me, threaten my sleep? Could it be the old magic, the earth magic, seeking a way in?

The Bees became my bridge to the Snake. In their hidden way, they revealed the old stories about the sacred serpent. She who moves through the earth. She who is pure creative power. Pure sexual life force. The embodiment of the divine feminine. In ancient Greece, the Oracle of Delphi, she who famously uttered prophecy, was known by two names: the Delphic Bee and the Pythia. She was a Melissae, a bee priestess, but she was also of the serpent, the earth-dragon. Pythia is a Greek name derived from Pytho, the old name for Delphi and our root for the snake species, Python. Pytho or Delphi was the center of Gaian mother culture; the navel of the world. This center point was represented by a stone, the omphalos, an egg-shaped carving guarded by Python and used in the uttering of prophecy.

John Collier [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

As Patriarchy made it’s way into Greek culture, the Pythoness became a monster. Apollo, the sun god, slew the serpent and Pytho became the Temple of Apollo. The divine feminine force was overthrown, shamed, violated and erased. So, we have another story of how we split ourselves from the natural world. How we took the wholeness of human expression and divided it, driving the stake down through our own sense of who and what we are. Divorcing man from nature. Woman from man. Sexuality from the sacred. The female form, she who knows the language of the serpentine flow, is exiled from the holy. Exiled to the point that today, in American politics around health care, simply being a woman is considered a pre-existing condition.

It is no wonder that I have been stalked through my dreams by the snake. From a shamanic view, to be bit by an animals in dreams, often signifies taking on the animal's specific powers or medicine. It is an invitation, never mind how terrifying. When we dig in to the storied myth-lines of our dreams, when we look at them as more than simply the psychological detritus of our day, we find breadcrumbs towards a fuller expression of self. We find that the antidote is venom, and the poison is our own disconnect between self and nature.

I talk to my bees. I ask them to teach me. I dream with them. I dream of them. They show me through sting, nectar, pollen and hum how to be a more embodied woman. Let's call it earth magic. Tomorrow I will set out on the trail, and have my conversation with the snakes: “You’re beautiful. I love you. I love the way you move. I will not harm you. I am afraid of you. If you choose to show yourself to me, let it be gentle. I love you.” Who knows if it does any good, but it places me firmly in my body, and I begin to weave my way back into Wilderness Self. Perhaps our wild feminine needs to be approached as such, aware of the long exile and the fear that comes from not knowing how to be around a force of nature that is so powerful. Even when that force is expressed through our very form.

You’re beautiful. I love you. I love the way you move. I will not harm you. So mote it be.

A Walk Through an Herbalist's Garden

Melissa bends low and plucks a small herb growing out of the cobble stones in front of her house. She holds it up to the light and shows me the tiny perforated holes in the leaves.

“That’s how you can tell it’s the medicinal St. John’s Wort.”

Note: Melissa is a fictitious name to respect anonymity of person and place. The name 'Melissa' translates to 'honey bee'. No photos were taken on location.

Melissa bends low and plucks a small herb growing out of the cobble stones in front of her house. She holds it up to the light and shows me the tiny perforated holes in the leaves.

“That’s how you can tell it’s the medicinal St. John’s Wort.”

She presses the sample in between a card about the medicinal properties of St. John’s Wort and offers it to me.

Melissa is a licensed herbalist living in a serene tucked-away valley in Southwest England. Her practice and gardens sit on one side of a happily meandering river, and on the other, there are two hives of bees. We stand in the early morning sunlight, watching the bees from the opposite side of the river. I don’t have to ask to know we wont be going any closer. These bees are to be left undisturbed. They are part of the land, as much as the hazels and the stones. Melissa regards them with an appraised respect. She never goes into the hives, and clearly does not keep bees for the purpose of harvesting and selling honey. The bees are part of the land and the land is rich with the plants that heal. They are wild hives.

Melissa takes us past the historical stone building on the property and into her gardens. She is wearing sturdy trousers, wellies and a thick wool sweater with a leather tool belt strapped around her waist where she can store her clippers and garden shears. She is every inch the embodiment of wise, practical and earth-centered. When we contacted her to find out if we could meet, she expressed that to visit is really about visiting the land, and since she lives on the land, she is more an aspect of the land itself.

After the bees, Melissa takes us by her wild garden. Once again, she doesn’t explain much, other than it is wild. I am reminded of a saying I once heard. “Always leave a part of your garden wild for the fairies." In this case, I think the fairies are the spirit of the land itself, the devas of the trees and river, made manifest in freely growing flowers and medicinals. It is a sage practice in that it honors both yourself as steward of place, and the land in its wild, infinite wisdom.

We pass through a bower and along the circuitous “rows” of her cultivated herb garden. I see carpeted thyme, raspberry, lavender and hawthorne. There are apple trees endemic to the valley, so old I feel like bowing to them. She teaches us the best way to pick apples and we harvest a pile of “cookers” and a pile of “eaters” to take home.

“You know an apple is ready to pick if your twist it, ever-so-gently, and it comes away. Never pull it.”

Inside her workshop, the light is dim, creating an immediately hushed, cosy environment. Here we find the transformation of her labors with the land into herbal medicines. On the table illuminated by a shaft of filtered light, is a large round basket of drying nettles. Nearby sits another basket fill with some kind of root, and above, herbs drying in bunches. Along the walls are bags and bags of neatly arrange herbs, and in the corner, there is a hearth with a kettle. Only in my dreams have I ever seen such a place. It is at once ancient and modern. I feel awed by the complexity of knowledge Melissa clearly possesses, while at the same time, comforted by the simplicity of being with the plants.

When speaking to her, I feel as though I am speaking to the voice of the valley. There is a deep listening in her presence that found often among those who live close to the earth. A listening that is more difficult to cultivate in our urban, technology-driven lives, but still possible. To listen deeply is to see true.

As someone who is currently not rooted to any one place, and is ultimately seeking a home (even if it’s more than one home in more than one country!), I find myself thinking about what it means to be truly rooted to a piece of land. I am lucky to travel the world and fall in love with landscape, people, cities and communities everywhere. I root myself in the act of being as present as I possibly can wherever I am. I am by no means a master as such things; that’s why it’s called a practice. In doing so, there are certain landscapes, just like certain people, that our bodies resonate to. Place where we receive an internal yes that has very little to do with the mind, and everything to do with the land. Earth reaching up as the body reaches down. How must it feel to know one piece of land so intimately that each flower, each root, each passing of the seasons becomes an extension of the self? The self becomes a reflection of the land: moulded, tempered and transformed.

I leave you with this quote by John Seymour, author and pioneer in self-sufficiency and environmental awareness:

“The ‘owner’ of a piece of land has an enormous responsibility, whether the piece is large or small. The very word ‘owner’ is a misnomer when applied to land. The robin that hops about your garden, and the worms that he hunts, are, in their own terms, just as much ‘owners’ of the land they occupy as you are. ‘Trustee’ would be a better word. Anyone who comes into possession, in human terms, of a piece of land, should look upon himself or herself as the trustee of that piece of land - the ‘husbandman’ - responsible for increasing the sum of things living on that land, holding the land just as much for the benefit of the robin, the wren and the earthworm, even the bacteria in the soil, as for himself.”

Silver Spring

England is full of natural springs. Every time I come here, I seek them out. There is nothing like drinking pure water, straight from the depths of hte earth. Almost all of the springs and wells in England are dedicated in one for or another to the sacred.

England is full of natural springs. Every time I come here, I seek them out. There is nothing like drinking pure water, straight from the depths of the earth. Almost all of the springs and wells in England are dedicated in one for or another to the sacred. As if often the case, most sacred springs were regarded as such by pre-Christian peoples who lived closer to the land and revered the spirit of place. Locations like mountain peaks, caves or a fresh water springs all had associations with a particular spirit, or the Great Mother goddess of the land herself. Over time many of these spirits became associated with specific Celtic gods and goddesses such as Sul, goddess of the thermal springs in Bath, or Brigid, goddess of healing, music, poetry and smith-craft. As Christianity moved across the land, most of these sites were appropriated by the Church, renaming the springs after the Virgin Mary or Christian Saints.

In Cerne Abbas, Dorset, there is a beautiful spring known as the Silver Spring, or officially as St. Augustine’s Well. It is located in a small tucked-away corner of the Cerne Abbas Abbey, and is shaded by over-hanging trees. On the hill beyond the well there is The Giant of Cerne Abbas: a huge image of a man with a giant phallus carved out of the chalk hillside. He is the main tourist attraction for Cerne, and the villagers regard him with both playful and serious respect. The Silver Well acts as the energetic balance point of the feminine, offering quietude, healing and solace to those who visit.

The bench next to the well has the words "Whoever Believes in Me" carved along it's side. Prayer tree/bush is just behind bench.

The spring’s most current patron saint was established by monks from the abbey in the 11th century. St. Augustine of Canterbury (d. 604 AD), said to be responsible for converting England to Christianity, supposedly struck the ground with his staff, thus producing water. No patriarchal symbolism there, eh?

On a plaque in the abbey grounds, another legend suggests St. Edwold came to the spring after dreaming of a silver well. While out walking the land, he happened upon a shepherd. He gave the shepherd silver coins in exchange for bread and water. In return, the shepherd showed St. Edwold the spring, which he recognized as the spring from his vision.

The Silver Spring in mid-winter flow, 2014. The water bubbles up from the back of the deeper pool.

The Silver well was associated with the feminine long before legends of patron saints and continues to hold folkloric traditions. This is made clear by the spring’s association with fertility and love. Women who wish to become pregnant drink from the well to cure infertility. Young women looking to find a husband used to the well as an oracular site or drank from the well while praying to St. Catherine.

Above the well, a rose bush stretches toward the water. Tied to it’s branches, are colorful ribbons and small rolled-up pieces of paper with prayers written inside. This is not an uncommon sight at holy springs in Britain. You find a similar tree on Wearyall hill and another over the Chalice Well, both in Glastonbury, Somerset. For me, these prayer trees symbolize a harmonious way humans interact with the sacred landscape, without needing to build a church on top of it to mark it as holy. I love the multi-colored prayers, ribbons fading in vibrancy as sun and weather do their part. A small exchange between human and spirit of place, an offering perhaps, a wish.

Prayers on the rose bush next to the Silver Spring, Cerne Abbas, Dorset.

To this I offer my own: a prayer for the water to return to California. I live in Northern California. Beautiful, wild, river and pine California, which is currently suffering from a horrendous drought. The week I left for Europe, two massive fires broke out, consuming vast amounts of land, homes and our beloved Harbin Hot Springs. Ultimately, my prayer is for people to initiate change. A change in our commercial agriculture system, that so bleeds the land of her water, draining California’s central valley aquifer and demanding a kind of production from the land that is unsustainable, to put it kindly. May we each do our part to find new and old ways to nurture our relationship to food, pollination and consumption.

The thorn tree on Wearyall Hill, Glastonbury, England.

Holy thorn before it was vandalized, 2010.

Maggie Daly in Connemara, Ireland, 2009.

![John Collier [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/55f313bae4b029b54a71c646/1500593162038-1FU8NJ7WHQFS7YM2RYMU/AriellaDaly_Pythia)